One might differentiate between at least three categories of Jewish recordkeeping and archival practices:

- First, the record-keeping practices which are found throughout Jewish history, but which were not necessarily termed “archives” by those who created or preserved the documentation at the time;

- Second, contemporary archival collections and repositories which are available for research;

- And third, historical collections which no longer exist, either because they were lost, destroyed, or split up and scattered (i.e. the materials may exist, but they are no longer held in a single collection or location). Oftentimes, these historical collections are now viewed as an “archive,” and certainly are studied as one, even if those who created them did not describe their activities in such terms.

This page will overview five of the most significant historical collections, i.e. those which either no longer exist as a single collection or which have been fundamentally transformed, and it will clarify some points about their current status and also offer a brief bibliography of further reading related to each:

- The Cairo Genizah, Egypt

- YIVO (prior to the Second World War, in Vilna, Warsaw, and elsewhere)

- Elias Tcherikower’s Mizrakh-yidisher historisher arkhiv (East European Jewish Archive), Kiev and Berlin

- Emanuel Ringelblum’s Oyneg Shabes archive (Warsaw), and other “ghetto archives” of the Holocaust era

- Gesamtarchiv der deutschen Juden, Berlin

The Cairo Genizah

Of the many Genizah repositories, the Cairo Genizah is certainly the most well-known. The story of its “discovery” by Solomon Schechter is particularly dramatic, and it has had a transformative impact on the study of Jewish history, perhaps only paralleled by the unearthing of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Cairo Genizah’s rich cache of documents has revolutionized our understanding of medieval Jewish culture, communities, and also global trade spanning the mediterranean world and into the Indian Ocean as well.

Initially established in the tenth century, the Cairene Jews broadened the prohibition against discarding documents inscribed with God’s name, and instead preserved anything written in Hebrew characters. In addition, the constant use and re-use of paper meant that many documents, manuscripts, and fragments stored in the Cairo Genizah actually contain multiple sources, including on secular topics (even if one part had a religious text leading it to be stored in the Genizah). The vast majority of the materials contained in the Genizah stem from the 10th to the 13th centuries, what is known as the classic Genizah period.

By the nineteenth century, the Cairo Genizah was stored in the Ben-Ezra synagogue in Cairo, and western travelers began visiting it. As early as 1864, reported in his memoir that he visited the Genizah. In the 1890s, after twin sisters Agnes Lewis (1843-1926) and Margaret Gibson (1843-920) discovered what they believed to be a Hebrew text of the book of Ben Sira (Ecclesiasticus), in 1897 Solomon Schechter carted off about 140,000 items from the Cairo Genizah to Cambridge—as his colleague Elkan Adler once put it, returning to England with “the spoils of the Egyptians.”[^]

This way of describing the process of the transfer of the Cairo Genizah indicates the basic Orientalist orientation of the entire operation. It is no mistake that these were mostly Jewish scholars based in the UK, and gathering the Genizah materials was directly connected to the broader British imperial project.

Schechter brought some of the Genizah materials with him to the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York City when he became its chancellor in 1901, and he published a number of important manuscripts. Schechter was primarily interested in the study of ancient manuscripts found in the Genizah, as opposed to historical documents and sources.

In the 1960s, S. D. Goitein published his monumental six-volume series A Mediterranean Society. Goitein was particularly interested in what he termed the “documentary Genizah,” the historical documents found among the manuscripts. He estimated that there were 20,000 items in the documentary Genizah and aimed to collect, catalogue, and transcribe them all.

The Cairo Genizah is today dispersed among more than 70 university libraries and special collections. A number of the most important collections and projects include:

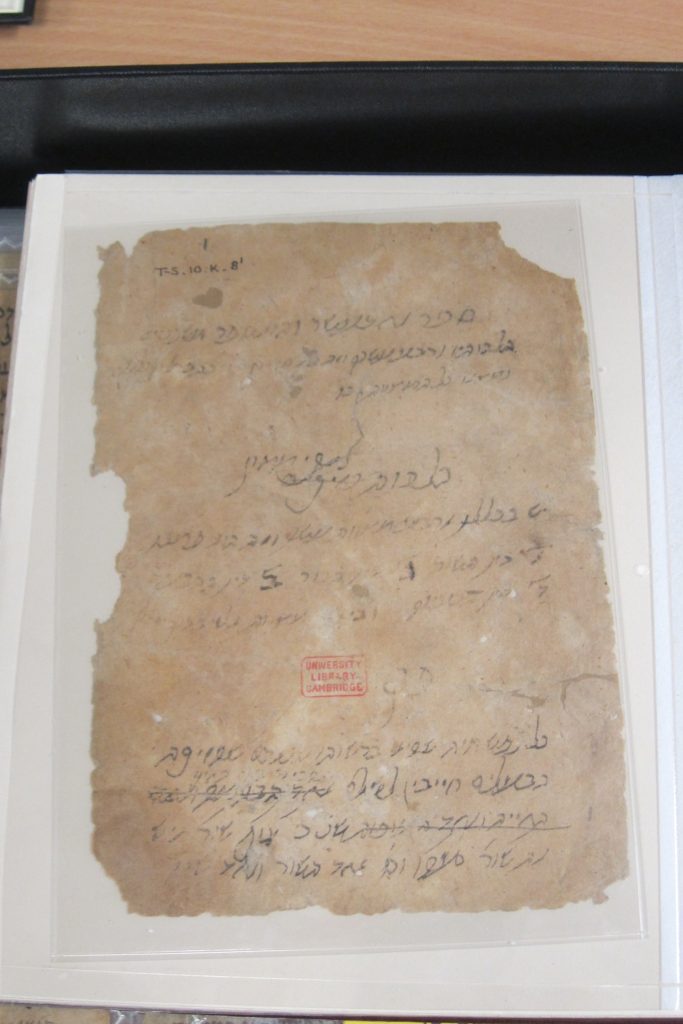

- The Taylor-Schechter Genizah Unit, Cambridge University. The “T-S unit,” as it is known, is the main Genizah research unit based at Cambridge and encompasses a number of collections including the Mosseri and Lewis-Gibson collections. It is based on the materials initially acquired by Solomon Schechter. Main contact: Ben Outwaithe

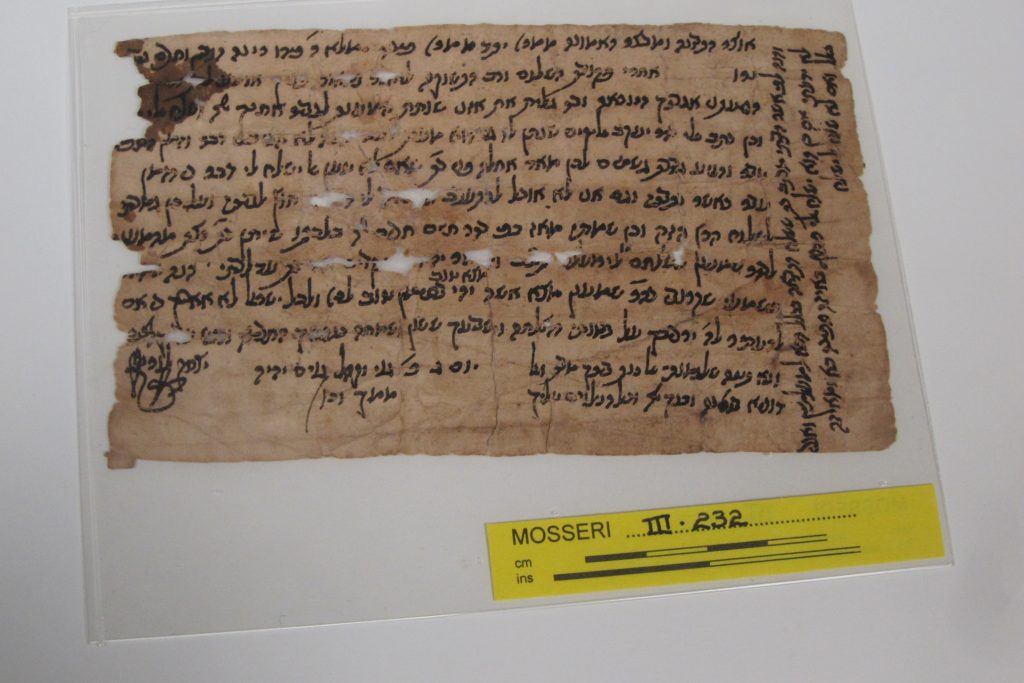

- The Jacques Mosseri Genizah Collection (held at the Taylor-Schechter Genizah Unit at Cambridge). In the 1910s, the Cairo-born Mosseri (1884-1934) worked with the materials that remained in the Ben Ezra synagogue, even after Schechter’s efforts to bring materials to Cambridge, and also files which were buried in the Jewish Bassatine cemetery. He gathered about 4,000 – 7,000 fragments. After Mosseri’s untimely death, the materials mostly inaccessible except via a hastily-produced microfilm from the 1970s. In 2006, Cambridge University procured these materials through a long-term agreement with the Mosseri family.

- The Lewis-Gibson Genizah Collection (held jointly by Cambridge University and Oxford University) was the

- Genizah fragments at Oxford Unviersity’s Bodleian libraries. A collection of about 4,000 Genizah fragments (25,000 pages) acquired since 1890.

- The Princeton Genizah Lab. S. D. Goitein (1900-1985) copied, collected, and transcribed a tremendous number of Genizah manuscripts from what he called the “Documentary Genizah,” i.e. differentiating between materials which are fragments from manuscripts and materials which were historical documents themselves. As he outlined in a 1970 article, he aimed to publish as many of these documents as possible.[1]Goitein, “On the Publication of the Documents of the Cairo Geniza,” 1970 Following Goitein’s death in 1985, much of the material was transferred to the National Library of Israel upon Goitein’s request; and scholars at Princeton led by Mark Cohen sought to digitize and study copies which were left in the United States. Cohen in fact reached out to the Israeli computer scientist and natural-language processing pioneer Yaacov Choueka about techniques for computer-assisted study (though their 1990 NEH grant was not approved). In recent years, Marina Rustow has led the Princeton Genizah Lab to utilize and study these materials.

- The Friedberg Genizah Project. In 1999, the Friedberg Genizah Project was launched with the aim, initially, of producing a union catalogue of Genizah fragments held at universities and libraries around the world. In the mid-2000s, Yaacov Choueka took over the project as it was re-envisioned as a way to digitize all of the Cairo Genizah fragments and create an online interface to browse, read, and study fragments and manuscripts held all over the world. Choueka and his team of computer scientists have created innovative algorithmic methods to identify “joins” between fragments, where multiple parts of a single document or manuscript are currently held by different institutions, allowing scholars to piece together again manuscripts which otherwise are scattered around the world.

Bibliography

- Marina Rustow, The Lost Archive: Traces of a Caliphate in a Cairo Synagogue

- Peter Cole and Adina Hoffman, Sacred Trash: The Lost and Found World of the Cairo Geniza

- Rebecca Jefferson, The Cairo Genizah and the Age of Discovery in Egypt: The History and Provenance of a Jewish Archive

- S. D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society

- S. D. Goitein, “The Documents of The Cairo Geniza as a Source for Mediterranean Social History”

- Stefan Reif, A Jewish Archive from Old Cairo: The History of Cambridge University’s Genizah Collection

YIVO

Note: This research guide differentiates between YIVO as a historical collection (i.e. from the pre-Holocaust era) and the present-day YIVO Institute for Jewish Research based in New York City.

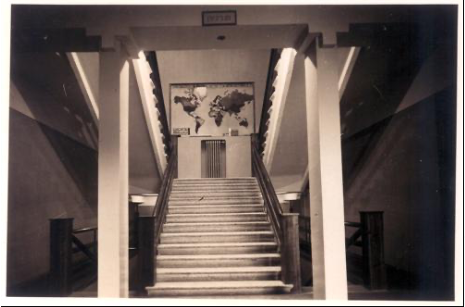

YIVO, or the Yiddish Scientific Institute, was formed in the winter of 1924-1925 in Vilna (then in Poland; today Vilnius, in Lithuania). It constituted a network of scholars with research centers based in Vilna, Warsaw, Berlin, and later Paris and New York City. YIVO was dedicated to the study of Yiddish culture and eastern European Jewry on its largest scale.

When YIVO was first established, it had four main “sections” or research groups: a philological section, which studied the development of the Yiddish language; an economic-statistical section, dedicated to contemporary social research; a pedagogical section, which aimed to develop Jewish education and in the 1930s created a graduate program called the “Aspirantur”; and a historical section, focused on the study of eastern European Jewish history.

The historical section was based in Berlin under the leadership of Elias Tcherikower, who had in 1919 spearheaded the effort to document the Petljura pogroms in Ukraine (what would become the Mizrakh-yidisher historisher arkhiv or East European Jewish Archive). As the head of the historical section, Tcherikower sought to gather materials on eastern European Jewish life, beginning with the files of Simon Dubnow, who at the time also lived in Berlin. In fact, the first meeting of the historical section met in Dubnow’s Berlin apartment. Later, Tcherikower moved to Paris and brought the historical section and its collections with him.

The historical materials and other archival collections that were at YIVO’s headquarters in Vilna were largely looted by the Nazis. Alfred Rosenberg’s looting task force, known as the Einsatzstab Reichleiter Rosenberg, took over the YIVO offices after the Germans occupied the city in June 1941. There, they forced Jewish scholars to assist in picking apart YIVO’s library and archives and sending the materials back to Germany for Rosenberg’s planned institute for the “study” of the Jews. A number of the Jewish figures smuggled books and other manuscripts out of the ghetto, what has become known as the “paper brigade.” However, in a great irony, it was the materials which the Nazis successfully looted and sent to western Germany that came under the American jurisdiction following the war which enabled them to be sent to New York City as part of the post-war restitution process, whereas the materials which were saved from the Nazis remained behind the iron curtain and were inaccessible to western scholars for nearly half a century. Today, there is an ongoing effort by YIVO in New York City in collaboration with Lithuanian libraries and cultural institutions to digitize the materials that remain in Lithuania so that they can “reunite” YIVO’s materials as a virtual collection.

YIVO exists today in New York City as a partner institutions at the Center for Jewish History, and is one of the premier Jewish archival institutions of the twenty-first century. However, we have listed it here in the section on historical archives because a fundamental distinction must be made between the operations of YIVO prior to the outbreak of World War II, and the New York center that emerged after the Holocaust. Two main points should be highlighted in regards to the archival status of YIVO before and after World War II.

- When YIVO was established, it never had a single, unified archive. Instead, each of the main research groups had their own archives — and they were often located in different cities, as was the historical section, based in Berlin. It was only after the destruction of YIVO in Europe, as part of the Holocaust, that the New York City center emerged as the clear leader of the YIVO network. It was in this context that Max Weinreich formed a single archival backbone of YIVO, as opposed to the disparate archival network of the pre-war period.

- YIVO’s archives from before the war have been split up. While a large portion of the pre-war files made their way to the United States following the war, a significant number of materials also remained in eastern Europe. As a result, we might think of YIVO in multiple ways — institutionally, the New York center sought to stress that they were the direct successor to the old YIVO headquarters in Vilna (especially in their memos to the State Department trying to gain access to Nazi-looted archives); and archivally, as a historical collection which has largely made its way to America but also has been scattered. In many respects the YIVO collections, as they were reconstituted in New York, are distinctive from those which existed before the war: first, in the immediate post-war years YIVO strove to document Jewish life in America, in addition to eastern Europe; and secondly, they came to include collections and other materials from Vilna which had never previously been a part of the YIVO collections, for instance the Strashun library which had never been a part of YIVO previously.

Bibliography

- Cecile Kuznitz, YIVO and the Making of Modern Jewish Culture: Scholarship for the Yiddish Nation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014)

- Marek Web, “YIVO Vilna to YIVO New York: An Archives Transformed,” in Jüdisches Archivwesen, ed. Frank M. Bischoff, Peter Honigmann (2007)

- Fruma Mohrer and Marek Web, “Introduction,” in Guide to the YIVO Archives (New York, 1998)

- Kalman Weiser, “Coming to America: Max Weinreich and the Emergence of YIVO’s American Center,” in Choosing Yiddish: Frontiers of Language and Culture, ed. Laura Rabinovitch, et al (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2013)

Mizrakh-yidisher historisher arkhiv

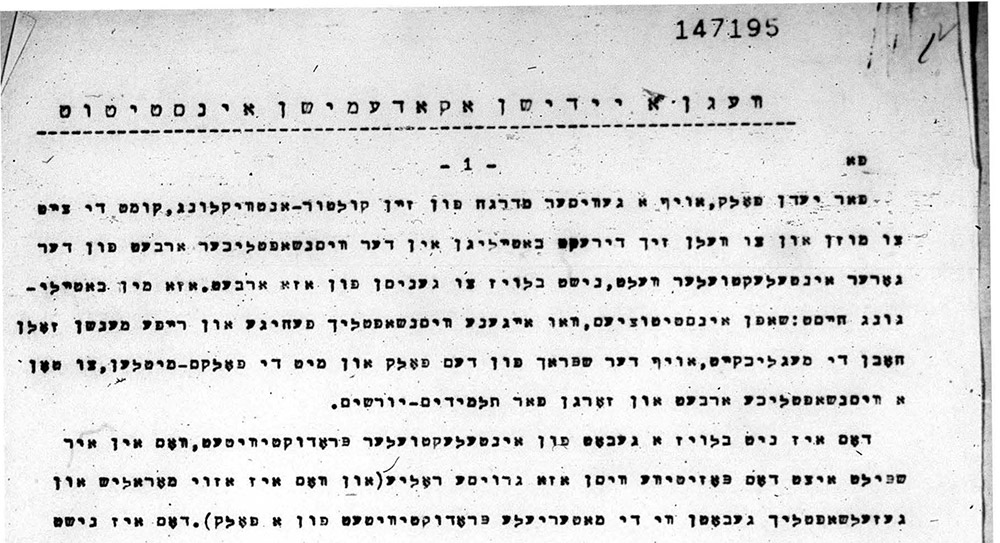

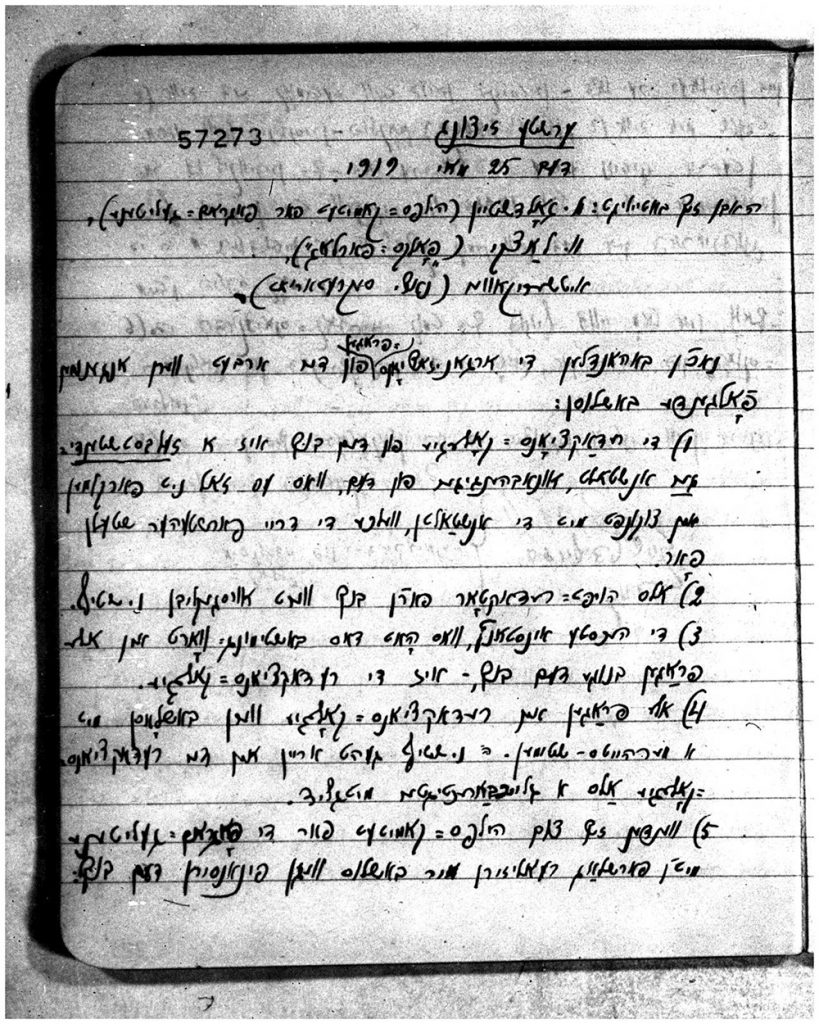

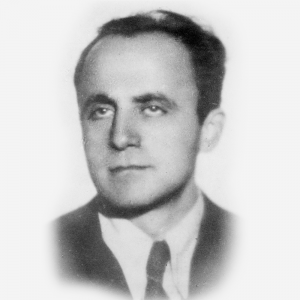

During the winter of 1918-1919, a series of anti-Jewish pogroms were committed by the battling armies of Simon Petliura and Antonin Denkin in Ukraine. Six months later, in May 1919, a group of Jews in Kiev led by the historian Elias Tcherikower (later the head of YIVO’s historical section) formed a committee to document the atrocities, the “Redaktsions-kolegia off tau Hameln un farefentlikhn di materialn vegn di pogromen in ukraine” (Editorial Borad to Collect and Publish the Material about the Pogroms in Ukraine), later known as the “Mizrakh-yidishn hostirishn arkhiv” or Ostjüdisches Historisches Archiv.”

Tcherikower and his committee called on Jews to submit reports of what they had witnessed to their central office in Kiev. The group’s aim, as the name indicated, was to use the collected materials to publish a history of the pogroms.

In 1921, the archive’s collections were smuggled out of Kiev and made their way to Berlin where it was dubbed the “Ostjüdisches Historisches Archive” (East European Jewish Historical Archive, or Mizrakh-yidishn historian arkhiv in Yiddish). Due to the acute hyperinflation in Germany, Tcherikower was able to publish his histories of the pogrom.

Later, the archive was used in the 1927 trial of Scholem Schwartzbard, who assassinated Symon Petliura at a Paris café. When Schwartzbard was brought to trial, Tcherikower’s archival documents were put forward as evidence of Petliura’s crimes, and in 1930 Tcherikower brought the materials with him to Paris when he moved there.

Tcherikower’s files are now held by YIVO in New York City, where they are accessible via microfilm and also have been digitized.

Bibliography

- Kelly Johnson, “Sholem Schwartzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin” (Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 2012)

- Efim Melamed, “‘Immortalizing the Crime in History…’: The Activities of the Ostjüdisches Historisches Archiv (Kiev–Berlin–Paris, 1920–1940),” in The Russian Jewish Diaspora and European Culture, 1917–1937, ed. Jörg Schulte, et al (Boston: Brill, 2012), 373–386

Oyneg Shabes Archive

During the course of the Second World War, Jews who were confined to ghettoes in eastern European cities created important caches of historical materials in order to document the Nazis’ crimes. The most famous of these was Emanuel Ringelblum’s “Oyneg shabes” archive, in the Warsaw Ghetto, and Jews in other major ghettoes developed similar archive projects, too.

The Oyneg Shabes archive was formed by Emanuel Ringelblum (1900-1944), a leading Polish Jewish historian. In Warsaw, Ringelblum organized the Aleynhilf (self-help) organization to employ the Jewish cultural elite, and which became the foundation of the Oyneg Shabes archive. From 1940 through 1943, the group gathered reports and other documents on the ghetto.

Three caches of documents from Oyneg Shabes were buried in the Warsaw Ghetto in large milk canisters. Two of the three were located after the war. The materials are now held at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

Alongside the Oyneg Shabes archive in Warsaw, Jews in other ghettos created similar archives, including in Lodz, Bialystok, and elsewhere.

Bibliography

- Kassow, Who Will Write Our History? Emanuel Ringelblum, the Warsaw Ghetto, and the Oyneg Shabes Archive (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007)

- Laura Jockusch, Collect and Record! Jewish Holocaust Documentation in Early Postwar Europe (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012)

- Klibansky, “The Underground Archives of the Bialystok Ghetto”

- Michael Unger, “ha-Ti’ud ha-Yehudi mi-geṭo Lodz”

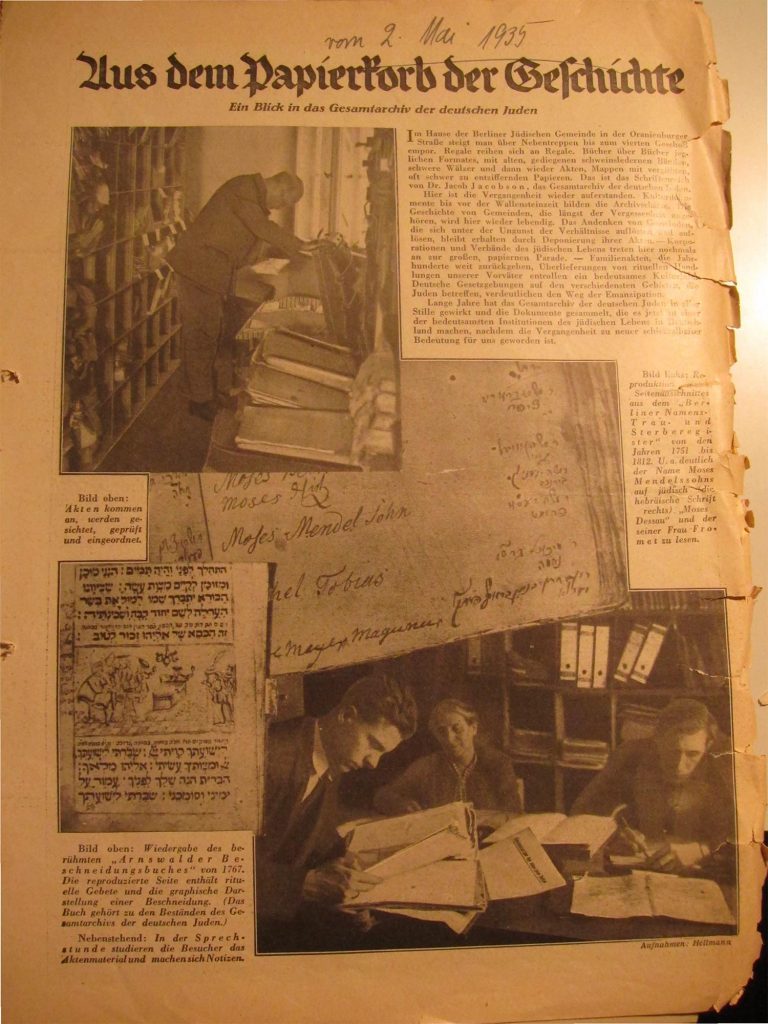

Gesamtarchiv der deutschen Juden

The Gesamtarchiv der deutschen Juden was the central archive of German Jewry, based in Berlin from 1903 to 1943. It was the first centralized, professionally-managed archive of Jewish history, and was formed under the aegis of the German B’nai B’rith and the Deutsch-Israelitische Gemeindebund, the union of German Jewish communities. It was led by Eugen Täubler from 1905 to 1920, and subsequently by Jacob Jacobson until he was deported to Theresientsadt in May 1943.

The Gesamtarchiv was a leading Jewish archive in large part because it stands at the center of a network of Jewish archives and archivists: For instance, Georg Herlitz, who served as Täubler’s assistant, formed the Central Zionist Archives in Berlin in 1919, and Josef Meisl, who worked in the Berlin Jewish community library down the hall from the Gesamtarchiv, founded the Jewish Historical General Archives in 1939. Also, many Jewish archives and archivists looked to the Gesamtarchiv as a primary example of a vision of creating monumental archives of Jewish life all over the world. Even those Jews who opposed archival centralization, like the rabbi Moïse Ginsberger in Alsace-Lorraine, were responding directly to the Gesamtarchiv and its collecting vision.

The Gesamtarchiv would hold the files over nearly 400 German-Jewish communities, and it became an important component of German Jewish life especially during the Nazi years. In this time, as Jews and non-Jews sought to provide “proof” of their racial status, the Gesamtarchiv’s usage increased dramatically. In addition, Nazi functionaries progressively took over the Gesamtarchiv as part of an effort to directly control Jewish communal institutions, given that the Gesamtarchiv contained tremendous amounts of practical data on Jewish communal administration.

During Kristallnacht in November 1938, the Gestapo specifically singled out Jewish archives as resources to try to preserve during the violence. In the months and years that followed the Gestapo and the Reichssippenamt (the Nazi office of “racial research”) confiscated Jewish communal archives and increased their control over the Gesamtarchiv. Jacob Jacobson was allowed to remain in charge nominally, but in reality he became a prisoner forced to conduct research for the Nazi authorities. In May 1943, the Gesamtarchiv was confiscated and transferred to the Geheimes Staatsarchiv (Privy State Archives) in Berlin–Dahlem.

During the course of the war, the Germans divided the materials between a number of archival caches. In 1950, about 50 crates of the Gesamtarchiv’s former materials were transferred to the Jewish Historical General Archives in Jerusalem (since 1969 the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People). The majority of the remaining Gesamtarchiv’s materials made their way to the Zentralarchiv in Potsdam, in eastern Germany, where they remained until the 1980s. In 1996, these materials were deposited at the Centrum Judaicum at the Neue Synagogue in Berlin.

Bibliography

- Jason Lustig, A Time to Gather: Archives and the Control of Jewish Culture1 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022)

- Barbara Welker, “Das Gesamtarchiv der deutschen Juden: Zentralizierungsbemühungen in einem föderalen Staat,” in Jüdisches Archivwesen, ed. Frank M. Bischoff and Peter Honigmann (2007).

- Peter Honigmann. “Die Akten des Exils: Betrachtungen zu den mehr als hundertjährigen Bemühungen um die Inventarisierung von Quellen zur Geschichte der Juden in Deutschland.” Der Archivar 54, no. 1 (2001): 23–31.

References

| ↑1 | Goitein, “On the Publication of the Documents of the Cairo Geniza,” 1970 |

|---|