The YIVO Institute of Jewish Research, today based in New York City, is one of the premiere research centers focused on eastern European Jewish history and culture. It is one of the partners of the Center for Jewish History, and it holds about 17,000 linear feet of historical materials in more than 1,800 record groups. Collections focus on Yiddish language, literature, and culture; eastern European Jewish history; the Holocaust; and Jewish life in the United States with a focus on eastern European migration in the time period 1880-1960.

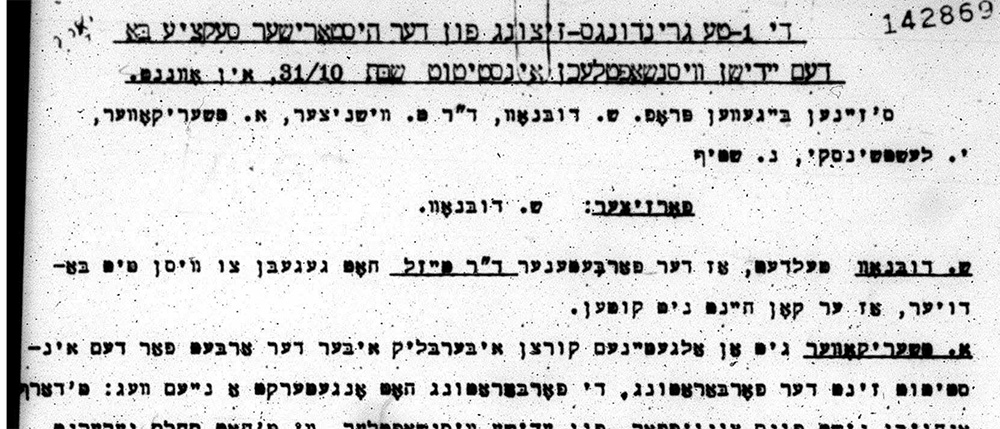

When YIVO was first established, in the winter of 1924-25, it was a network of scholars and research centers dedicated to the study of eastern European Jewish history and culture, with its headquarters in Vilna (today Vilnius, Lithuania) and branches in Warsaw, Berlin, and elsewhere. It had four major sections (departments) including its philological section, economic-statistical section, pedagogical section, and historical section.

YIVO’s founders, including Nokhem Shtif and Elias Tcherikower, saw their work as a continuation of the great scholar Simon Dubnow (1860-1941)—indeed, Tcherikower’s historical section held its first meeting in Dubnow’s Berlin apartment. A generation before, in 1891 and 1892, Dubnow had publicly called on Jews throughout eastern Europe to gather historical materials, leading to the emergence of the ‘zamlers’ or collectors. Now, the YIVO sections continued this tradition of folk collecting, calling on everyday Jews to gather materials, fill out surveys, and submit reports on all aspects of Jewish life in eastern Europe. As a result, YIVO developed a number of significant archives and collections in the years prior to the Second World War, the most significant of which were in Vilna, Berlin, and later in Paris after Tcherikower relocated there in 1930.

Alongside the research centers in Europe, groups of Jews in the far-flung eastern European diaspora created their own branches of YIVO, notably in New York and Buenos Aires. In 1939, both of these groups formed archives of their own, the Central Jewish Library and Press Archives (New York) and the Central Library and Archives (Buenos Aires).

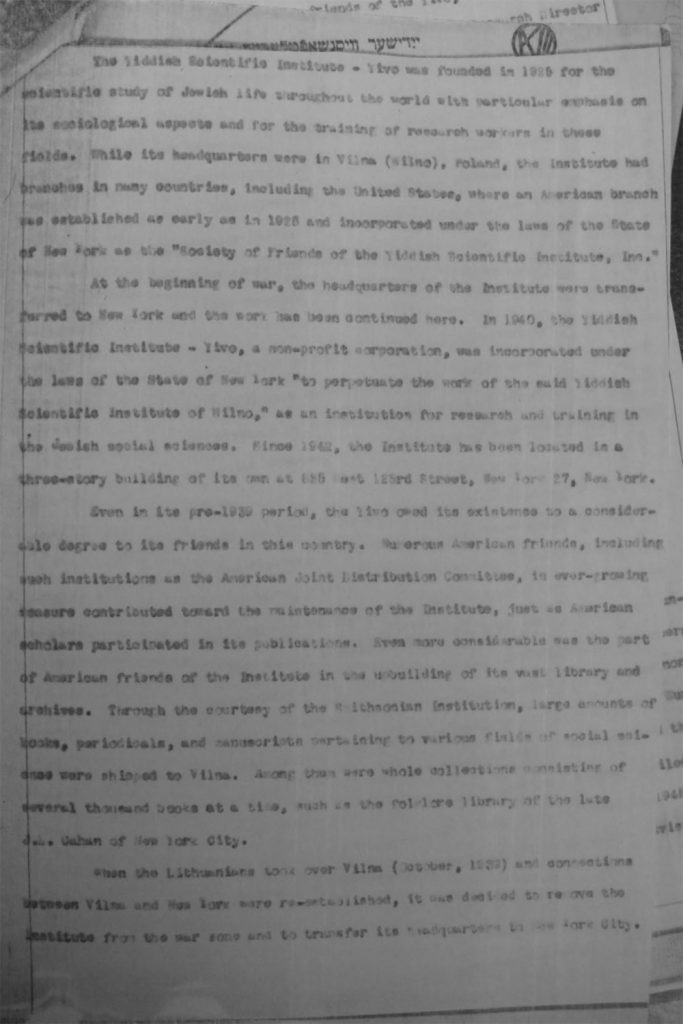

The New York branch, when it was formed in 1925, was mostly a fundraising arm in support of YIVO in Europe. With the outbreak of World War II and the destruction of European Jewry in the Holocaust, like American Jewry at large, YIVO in New York was thrust into a new position of leadership, under the leadership of Max Weinreich (1894-1969).

Prior to the war, Weinreich had been the research director of YIVO in Vilna. In September 1939, he found himself in Copenhagen attending a conference with his son Uriel. Stranded there for six months, he eventually secured a visa to come to the United States; alongside Elias and Riva Tcherikower, who also made their way to New York at the same time, there was now a cohort of leading YIVO figures. There, Weinreich took over YIVO’s New York branch and remade it as a leading research center.

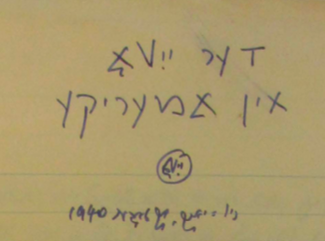

In America, Weinreich set out a new mission for YIVO—as he put it in a 1940 memo, “YIVO in America,” dedicated to documenting Jewish history in eastern Europe, research, and teaching. However, they also hoped that they might re-establish YIVO in Vilna. In the first issue of the Yedies fun yivo (YIVO News) published in the U.S., in November 1943, they asked for books for their library: “Send us everything! We need duplicates and triplicates for our book fund for postwar Europe.”

As the full scale of the Holocaust came into view, however, Weinreich and other YIVO leaders shifted gears towards creating a a new scholarly center in America. Their focus would now be on documenting eastern European Jewish life as well as the immigrant experience and labor struggles in America, beginning with an autobiography competition. YIVO also sought to apply the same style of studying contemporary Jewish life to the American context.

After the war came to an end, YIVO was also able to acquire a great deal of its former archives and libraries. The Nazis had infamously looted Jewish libraries and archives across Europe, including YIVO’s Vilna headquarters, and brought these materials to Frankfurt am Main, which was now in the American zone of occupation. The main collecting point for these looted archives, books, and other cultural treasures was the Offenbach Archival Depot. There, Koppel Pinson, Col. Seymour Pomrenze, and others sifted through the boxes to find what was there—and discovered a tremendous cache of files formerly held at YIVO.

Weinreich quickly reached out to the State Department and other government officials to argue that these files should be transferred to New York, instead of being returned to eastern Europe as per the Geneva Conventions’ stipulations that war booty be returned to the location of origin. As Weinreich articulated in a 1946 affidavit, he saw YIVO in New York not just as a successor to YIVO in Vilna, but as a direct continuation of the very same organization with a mission of perpetuating its activities, meaning that the files should be “returned” to them. On this basis, YIVO received these materials, constituting about 70% of its former archives, as well as the Strashun Library, which had been based in Vilna but not a part of YIVO.

In the decades that followed, YIVO continued to collect historical materials, adding to its original records on eastern Europe with materials on American Jewish history. As longtime YIVO archivist Marek Web put it, it was a kind of campaign for records by creating an army of volunteer collectors. This was another way in which YIVO saw itself in the great tradition of Jewish folk collecting, from Dubnow’s zamlers to those of YIVO, both in eastern Europe and then America. However, as Web noted in a 1980 presentation at the meeting of the Society of American Archivists, they were now shifting away from an active collecting program and “campaigning” for records, and now saw themselves focusing on their archival mission of describing and making the materials available for research.

However, YIVO’s efforts to actively gather historical materials was by no means over. In the late 1980s, it was discovered that a portion of YIVO’s former Vilna files had remained in Lithuania. During the Cold War, these files were stored at Lithuania’s State Book Chamber at the Church of St. Yuri; later they were transferred to the National Library and the Central State Archives, and also a cache of files were found at the Wroblewski Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences. As a result, in the 1990s YIVO sought to claim these files and bring them to the United States. While they were unable to acquire them permanently, YIVO did bring them to New York for microfilming, eventually returning them to Lithuania. Beginning in 2015, with the support of the National Endowment for the Humanities, YIVO and the Lithuanian library and archive institutions have been scanning these materials and creating a unified virtual collection, the Edward Blank Vilna Collections, which will make these files available digitally.

Research Notes

Researchers can consult the online Guide to the YIVO Archives, which offers further details on the scope and history of the collection as well as the ability to browse collections and consult finding aids.

YIVO’s archives are accessible at the Center for Jewish History. Most collections are housed on-site, but they sometimes have to bring in materials from warehouses in New Jersey. Researchers should ensure that they have built time into their archival trip to accommodate if this is the case.

files are generally labeled RG-xx (record group). Those in RG 1-99 are the “Vilna collection,” i.e. materials which were held in Europe (though not all of them in Vilna, for instance Elias Tcherikower’s files, RG 82).

With few exceptions, YIVO does not allow photography of their archival materials. Scholars, however, can use the microfilm machines which have scanning capability.

Further Reading

- Jason Lustig, A Time to Gather: Archives and the Control of Jewish Culture, ch. 6

- Fruma Mohrer and Marek Web. Guide to the YIVO Archives. New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1998.

- Kalman Weiser. “Coming to America: Max Weinreich and the Emergence of YIVO’s American Center.” In Choosing Yiddish: Frontiers of Language and Culture, edited by Laura Rabinovitch, Shiri Goren, and Hannah S. Pressman, 233–52. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2013.

- Cecile Kuznitz. YIVO and the Making of Modern Jewish Culture: Scholarship for the Yiddish Nation. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Marek Web. “YIVO Vilna to YIVO New York: An Archives Transformed.” In Jüdisches Archivwesen: Beiträge zum Kolloquium aus Anlass des 100. Jahrestag der Gründung des Gesamtarchiv der deutschen Juden, edited by Frank M. Bischoff and Peter Honigmann, 143–56. Marburg: Archivschule Marburg, 2007.

- Dan Rabinowitz. The Lost Library: The Legacy of Vilna’s Strashun Library in the Aftermath of the Holocaust. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2019.