- Introduction

- Jewish Recordkeeping Throughout History

- The Development of Modern Archives for Jewish History

- Toward an “Archival Perspective” on Jewish History

Introduction

What is the history of Jewish archives? In a word, it is Jewish history, and it reflects the developments of Jewish culture across the ages on its largest scale and scope: On a concrete level, the historical materials that have made their way to our own day are what remains of the Jewish past, without which the study of Jewish history and culture would be greatly impoverished; their pathway through history manifests the broader history that Jews have traversed. Moreover, Jews’ collecting practices have reflected the dynamism of their history throughout the world: Markus Brann may have claimed incorrectly a century ago that a “lachrymose history” of the Jews, characterized by massacres and expulsions, had not enabled Jews to keep archives; by contrast, specifically because Jews were actively driving their community and individual lives, they always produced and preserved records of these activities. Moreover, these recordkeeping practices were closely related to the cultures and societies among whom they lived. And the archives are a testament to the Jews’ great diasporic history. Wherever Jews moved from place to place across the centuries, they have left the traces of their lives and cultures.

The history of Jewish archives is also a story of tremendous proliferation, particularly in modern times when Jews sought to study their history and preserve their past in times of great turbulence. Ezechiel Zivier, the German Jew who first proposed the creation of a central German-Jewish archive, remarked in 1903 that “every great people wants to have an archive of their antiquities.” In the nearly 120 years since then, Jews the world over have exhibited this exact impulse to collect the materials of their past, resulting in the existence of a dizzying multiplication of archival repositories, institutions, and projects—both before the Holocaust, in its immediate aftermath, and into our own day. These archives have provided practical, documentary resources for the rich and fruitful study of the Jewish past, what we have termed a “time to gather” that reflects both the proliferation of archives and the specific impulse to bring together the forces and resources of Jewish culture on a larger scale.

A Brief Outline

This overview of archives in Jewish culture aims—as briefly as possible (after all, one could write an entire book or more on the history of Jewish archives)—to provide practical introduction and historical context to how we arrived at today’s vast proliferation of Jewish archives, which we have presented in the form of a directory of nearly 200 contemporary archives of Jewish history. The central question is: How did we get here? And what does this all mean?

Consequently, it has three main sections:

- First, we will detail some forms of Jewish recordkeeping practices and their connection to the broader development of Jewish history across the centuries, as we understand recordkeeping and archives as a central element of Jewish life at large.

- Secondly, we will highlight the development of archives in modern times, when Jews specifically looked to create archives—as archives. That is to say, around the turn of the twentieth century, Jews began specifically gathering records under the framework of “archives.” It is a key argument of this overview, like of A Time to Gather, that Jews’ specific choice to frame these collecting activities as archives constituted a marked change in the way that Jews engaged with these materials, and with their history at large.

- Third and finally, we will illustrate ways we might speak of an “archival perspective” on Jewish history: Archives and records are just as the products of historical activities, but have actively contributed to the ongoing development of Jewish life and culture throughout the ages. That is to say, the place of records and archives in Jewish culture showcases the ways that archives have never been purely passive repositories. The process of creating, storing, and preserving documentation was part and parcel of the daily realities of communal administration, business activities, emerging social and political movements, and so on. This is true both throughout the centuries when Jews’ records were directly related to their settlement (e.g. in the case of medieval charters and privileges) and also in modern times. Jews did not just collect for the planned study of the past, but as part of the broader social and cultural forces of their own day. This reality of the active role of archives stands at the heart of the idea of the twentieth century as “a time to gather” in Jewish culture: Archiving materials was not just in the service of the formation of modern Jewish studies, but has been, and remains, part of the ongoing unfolding of Jewish history itself.

Altogether, this guide aims to explain how the development of archival forms relates to the broader Jewish history that produced these records and other historical materials, and ultimately how these traces of history have made their way to today. It will also outline the emergence of modern archival practices in Jewish culture and the efforts to preserve historical materials, a “time to gather” in Jewish culture.

Recordkeeping Throughout Jewish History

In 1917, Markus Brann, a history professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary (Jüdisch-Theologisches Seminar) in Breslau (today Wrocław), declared that Jews had not kept archives throughout their history: “Due to our restless wandering,” he reflected, “we Jews have had no leisure to create well-ordered archives and to preserve written sources.” Forty years later—a Biblical generation that saw the destruction of European Jewry and the remaking of the landscape of Jewish life around the world—Israel’s state archivist Alex Bein told a strikingly similar story at the 1957 inaugural meeting of the Israel Archives Association. There, he claimed, as he would repeatedly, that Jews in the Diaspora had long lacked archives.

Brann and Bein were not alone among professional archivists and scholars who bemoaned a lack of Jewish archives, and claimed that Jews had historically not preserved their past—and that it was necessary for these materials to be gathered into new historical repositories and archives. This is the central paradox of the proliferation of Jewish archives in modern times. Despite the claims of archival figures (who had their own professional self-interest in articulating their activities’ novelty and necessity), Jews had clearly gathered and preserved historical records throughout their history. Otherwise, there would have not been anything for modern-day collectors to gather in their new repositories and archives! At the same time, there was a marked shift in the ways Jews in modern times preserved the materials of their history, now increasingly under the umbrella of archives. It is in the context that we can look toward rich, diverse, and dynamic collecting and archiving traditions in Jewish cultures throughout history. It is this proliferation of archives that has made available such innumerable riches of Jewish history and makes it possible for us to study Jewish history and which offers the history of archives as a tremendously fruitful avenue for understanding modern Jewish culture.

When Brann and other twentieth-century Jewish scholars claimed Jews had lacked archives throughout their history, it reflected their own sense of what an “archive” was, as a distinctly modern and western phenomenon, and they thus discounted earlier activities as “non-archival.” In reality, Jews have had diverse recordkeeping practices throughout history, and archives have been a continually important feature of Jewish cultures.

Archives in Ancient Israelite and Jewish Cultures

It is beyond a doubt, for instance, that the ancient Israelite kingdoms kept records and archives of their administration, just like other ancient Near Eastern polities. (See, for instance, the discussion in Ernst Posner’s landmark book Ancient Archives.) Ancient Diaspora communities also kept caches of records, which have been used as archives by modern scholars, like the Yadania archive at Elephantine.

In another mode, we might consider the Biblical texts as a sort of archive themselves. This notion is especially notable in the context of the documentary hypothesis’s supposition, widely accepted by scholars, that the Biblical text was stitched together from a series of documents (both in a literal sense of parchment, and also textually speaking via redaction). For instance, the “discovery” of the Deuteronomic text during the seventh century BCE implies that there was a repository of texts in the Temple—a.k.a. an archive—where it might have been “found.”

Genizah Practices

Recordkeeping practices are also deeply ingrained in Jewish religious traditions. In fact, when people think about “Jewish archives,” one of the first traditions that comes to is the genizah (plural, genizot).

In the Bible, the Hebrew root GNZ (גנז) referenced the chests and treasuries of kings and other kinds of repositories (perhaps as a loan word from Farsi). And in modern Hebrew, it was adapted for the technical term for archivist, ganzakh (גנזך) and the formal term for archive, ginzakh (גינזך), as in Israel’s State Archives (ganzakh ha-medinah, גנזך המדינה).

The Genizah tradition stems from the Talmudic prohibition against the destruction of holy books and Torah scrolls. Instead, Jews were instructed to deposit such texts in a storage space, known as a Genizah, usually kept in a corner of the synagogue. The Genizah’s contents were to be buried every so often, usually every seven years.

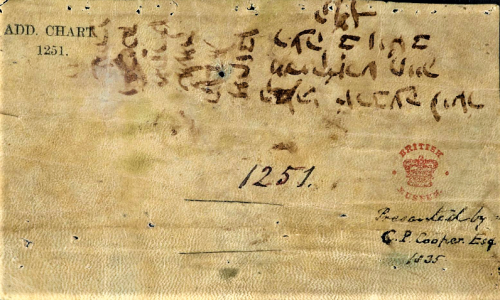

The Cairo Genizah is definitely the most famous such repository, in part because such a rich collection of material was preserved there due to the climate and other factors. In fact, the “discovery” of the Cairo Genizah can be characterized as one of the most important developments in modern Jewish studies in the past 150 years, alongside the unearthing of the Dead Sea Scrolls: It may not have been an “archive” in the eyes of those who stored the documents in the Genizah, but it has become one of the most important archives for those who study the mediterranean world and beyond.

While the Cairo Genizah is the most well-known such repository, the Genizah tradition goes far beyond medieval Egypt. Jews around the world have kept Genizot, and there have been efforts to reconstruct them. In fact, the terminology of the “Genizah” has been applied to the general process of trying to uncover and reconstruct scattered documents, for instance of Jews in Europe and Jews in Iraq.

Charters and Privilegia

One can also identify another distinctive genre of records in Jewish cultures, and one that has had a direct impact on Jewish history, the manifold charters or privileges (privilegia). These documents offered a certain security for Jewish communal life in medieval Europe by laying out the rights and privileges, and also the obligations, of Jews in a particular place or polity. They existed both in terms of local charters, which related to a specific city or town, or general charters for entire countries.

In one of the earliest such documents, in 1084, the Bishop of Speyer, in the Rhineland, presented the Jews with a Latin charter.. It outlined protections offered to Jews in the village, and also Jews’ autonomous status in control of certain internal affairs. For instance, the leader of the Jews would “adjudicate any quarrel,” just as the mayor did for the burghers. The charter also dictated that Jews should pay certain taxes and payments for such protection.

As the Speyer charter indicated, one goal of such charters was to entice Jews to move to a new place. This goal is characterized by the well-known Charter of Kalisz (1264), which offered Jews protections and rights for moving to Polish lands and contributed to the wider migration of Jews towards eastern Europe in the following centuries.

Such charters and privilegia might seem to set the Jews apart from the broader feudal systems of medieval Europe. But most interestingly, these documents are actually characteristic of the feudal system at large, which was centered around (a) distinctive rights and privileges for each individual sub-group in society, rather than uniformity; and (b) the chartering of specific groups and associations like corporate bodies, guilds, universities, and Jewish communities, too. These charters thus were the basis for autonomous Jewish self-administration (in its various forms and to different degrees), just as the charters for universities allowed for the autonomous administration of justice, as in the case of “student prisons” and the like.

Records of Business and Especially Debt Receipts

When Jews developed and participated in business activities of all kinds, they also produced records related to their work, whether we look to correspondence between business networks, account books, and bills of exchange. In this respect, the entire economic history of the Jews is closely tied to the process of creating business archives.

There are two types of documents and records that are especially important to consider in this context: debt receipts and bills of exchange.

In medieval and early modern Europe, lending money at interest was one of the most important business activities Jews participated in. Jews were not restricted only to this activity, as is popularly believed, but it was an economic realm in which Jews were one of the few groups that were allowed to operate due to the Church’s longstanding doctrine that Christians were not allowed to lend money at interest. Jews, by contrast, were allowed and even encouraged to pursue this line of business, because any thriving economy requires some sort of credit, and because it was also a mechanism by which the state was able to raise funds. Jews, as outsiders without political or military power, were also useful in this role because they were dependent upon the ruler, who could step in and annul or adjust debts if desired.

This entire phenomenon played out particularly in medieval England, where Jews were the sole group that could be relied upon to pay taxes, leading them to be described to as the “Royal Milkh-Cow.” In the interest of raising taxes, the English kings actively encouraged Jews to lend money to the nobility, which was taxed heavily; they created an entire recordkeeping system for this specifically, leading Richard I (r. 1189-1199) to insist debt receipts be kept in triplicate, with the royal treasury keeping one set of these records. And in a fascinating turn of events, it was these records, and the taxation apparatus they represented, stood at the center of the eventual expulsion of the Jews from England and the institution of semi-constitutional government: English politics in the thirteenth century was characterized by a struggle to raise taxes from the nobility, with the Magna Carta of 1215 (another charter!) resulting directly from the nobility’s unwillingness to pay taxes. And then, the 1290 expulsion of the Jews again related to the question of the nobles’ tax and debt obligations; among the reasons for expelling the Jews, one prominent one was that the nobles—who owed significant amounts of debt to Jewish moneylenders—wanted the Jews removed, and their debts from the books, too. That is to say, the English nobles acquiesced to new taxes only on the condition that their debts to the Jews be confiscated by the crown and heavily restructured. Ironically, the English nobles did not hold their own debt records, as they were kept by the king’s treasury; they actually owed less in debt to Jewish lenders than the new tax obligations that they took upon themselves.

In addition, one can look to bills of exchange as an important component of Jewish business activities. In fact, as Francesca Trivellato has argued in a recent book, this genre of business record—which allowed for the transfer of funds and goods safely across long distances—was believed incorrectly to be a “Jewish” document. In this respect, we can understand bills of exchange to be part of not just the development of modern economic activities, but also a component of the wider history of Jewish archiving activities: the production and usage of these documents was important for Jews who were developing trade and business networks across long distances, and also led to certain anti-Jewish stereotypes about modern economic development.

Altogether, we can look to business archives as an important part of Jewish history: and, like charters, a set of records which not only resulted from the developments of peoples’ lives and historical choices, but also directly affected the ongoing development of Jewish history.

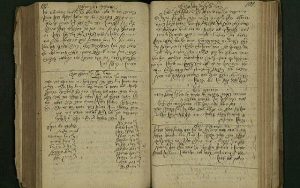

Communal Records and Pinkasim

In all of the various forms of autonomous Jewish communal administration, Jews also have kept records of their internal affairs. Many Jewish communities thus produced record-books relating that compiled receipts and expenditures, the rulings of rabbinical courts (bet-din), births, deaths, marriages, and divorce, and more.

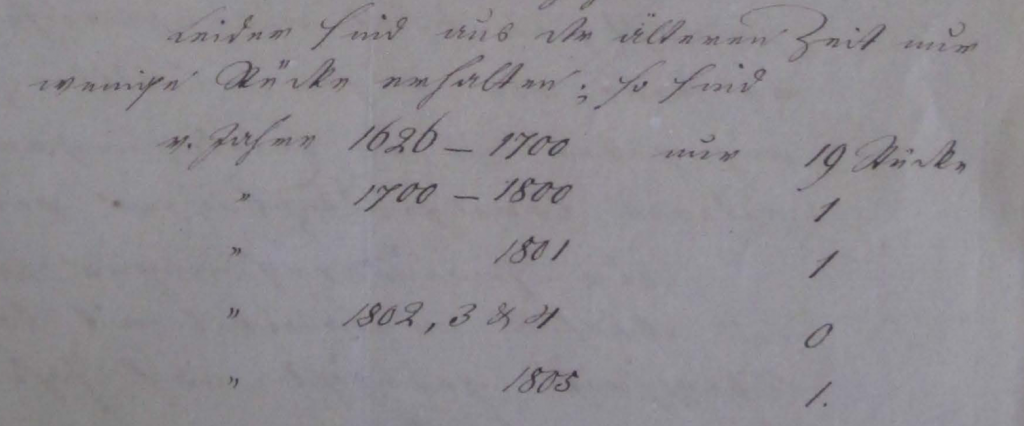

These record books came to be known as pinkasim (singular, pinkas). They were long produced by Jewish communities and constitute one of the most important recordkeeping traditions that manifest the specific internal organizations of the Jewish community (Heb. Kahal) prior to modern times.

Jewish Archives in Modern Times: The Development of Archives as Archives

Many of these recordkeeping practices have continued into modern times, but alongside them we can also identify a number of archival shifts that are deeply connected to the changing place of Jews in the societies where they lived. In particular, Jewish recordkeeping practices were greatly impacted by the changing relationship between Jews and the state, and also these records increasingly came under the rubric of archives.

Jewish Records and the State

In many respects, the records of Jewish life and practices of record-production in Jewish cultures have always been deeply tied to the state and its archival power. Charters and privileges were themselves the product of the state and were inscribed with a wax seal to ensure their authenticity and the state power thereby inscribed within them; and many records relating to Jewish life have been found in state archives both before modern times and more recently, too. For instance, police records are an important source of information on Jewish political activities, especially in eastern Europe, as the police sought to infiltrate and surveil Jewish organizations and leaders.

There are a few additional ways we can understand the changing relationship of the state with the Jews in modern Europe as having a direct impact on Jewish recordkeeping practices and archival preservation.

In particular, the growth of the centralized, interventionist, tutelatory state in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries effected a seemingly paradoxical double-shift on the relationship of Jews with records, which reflected the internal contradictions of emancipation and the demands thereby placed upon Jews.

First, as states increasingly centralized political power and tried to create unified sets of regulations that applied to all its residents and transform subjects into citizens, it is certainly true that charters, and the broader phenomenon of privatization of law they created, would be less influential, and these documents would be less pertinent to peoples’ day-to-day lives and become a part of history. Secondly and simultaneously, the new-found aspiration towards direct ties between individuals and the state meant that there was an entirely new documentary apparatus that controlled this relationship, as the state now produced identification documentation like passports and the like.

Moreover, states’ increasing efforts to intervene in the lives of their citizens and “productivize” them had a direct impact on the Jews. Even though Jews were theoretically treated as individuals, Jewish communities were also called upon to document their population in the aim of supporting the state’s social engineering programs. For instance, Joseph II’s 1789 edict of toleration for the Jews of Galicia instructed Jews to register members of their community. This was part of an effort to make Jews “legible” to the state and aid in policymaking due to knowledge of the population, but it was tied to military conscription, too.

All in all, it seems that in many instances the demands of emancipation and “modernization” were connected with the idea that Jews should have an official archive of their records. This was the case in Vienna, for instance, when in 1816 the Jews were instructed to form an archive for their historical documents (it would only be officially created in 1841 under the leadership of Ludwig August Frankl).

In imperial Russia, too, we can see the intervention of the state into Jewish life as having a direct documentary output: The creation of the “state rabbis” in the 1840s and beyond was directly tied to an effort to document the Jews, as these rabbis’ main occupation was maintaining metrical books with Jewish marriage, divorce, birth, and death records.

All this is to suggest that Jewish archival and recordkeeping practices changed dramatically under the new regime of centralized European states. The archival scholar Robert-Henri Bautier once famously declared that in modern times archives shifted from “arsenals of state power” to the “laboratories of history.” However, states continued to wield archives and records as arsenals of power, as they still do. In this respect, it is not surprising that as Jews turned towards their own national aspirations at the turn of the twentieth century, they also saw archives as something critical to create.

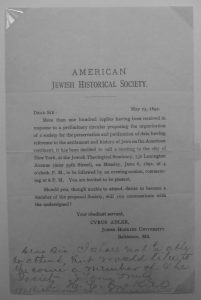

Jewish Historical Societies

Another important archival development in modern times was the formation of the first Jewish historical societies and their concomitant efforts to document Jewish history and culture. In the last few decades of the nineteenth century, Jews created historical societies in France (1880), Germany (1885), England and the United States (1892), and beyond. These historical societies usually sought to articulate the notion of Jews’ long history in the various places where they had lived, and published historical articles as well as primary sources. However, they often did not have an “archive” of their own—at least not in those terms. For instance, the Historsiche Commission of the Deutsch-Israelitische Gemeindebund (1885) sought to publish historical materials on German Jewry, but it would only bet 20 years later that the DIGB helped to form the Gesamtarchiv der deutschen Juden, the first institutionalized archive of Jewish history.

In fact, some of the leading historical collecting activities of this time actively eschewed archives. For instance, in 1892 Simon Dubnow famously appealed to the Jews of eastern Europe to preserve the materials of their history. But as Dubnow put it in his cri de coeur, he aimed to salvage documents from the archive rather than create one of his own.

What is fascinating about the development of these historical societies and collecting activities of the late nineteenth century was the way that we find that there are not archives where we would expect them to be; leaders of these historical societies did discuss doing research in state archives, but by and large they did not use the language of “archive” to describe the collections they themselves were constructing. But a half-century later, by 1942, we see archives everywhere—especially in the places where we might not expect.

Documenting Tragedy and the Rise of the “Archive”

This transformation of Jewish collecting into the archive is a remarkable shift over the course of a half-century. In the waning years of the nineteenth century, Jews sought to collect materials and document pogroms and other atrocities of their own day, an important and distinctive response to tragedy.

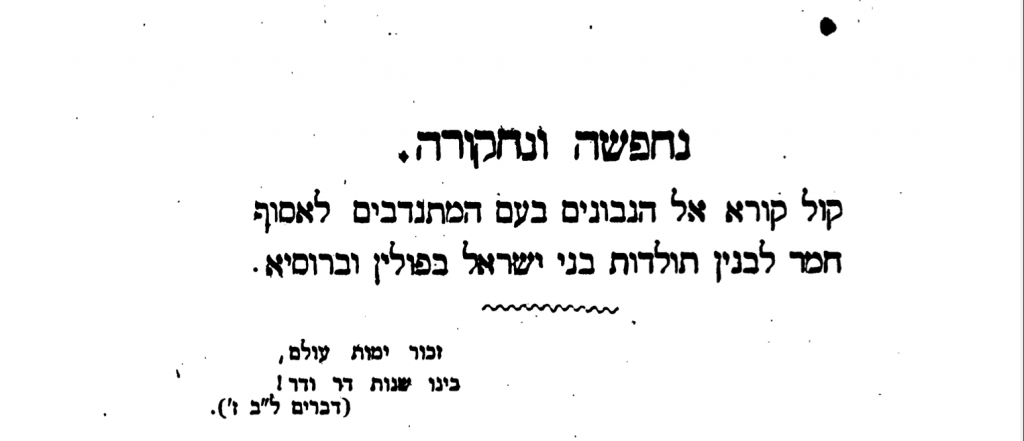

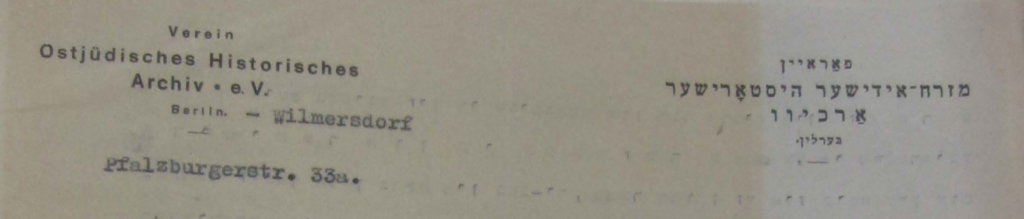

For instance, one can look to the group Heye ‘im pefiot (היה עם פפיות) sought to circulate news of the 1881 Russian pogroms, Simon Dubnow’s efforts to document the 1903 Kishinev pogrom, and later Elias Tcherikower’s Mizrakh-yidishn historishn arkhiv that recorded the Petljura pogroms of 1918-19—and eventually the Emanuel Ringelblum’s Oyneg shabes “Ghetto archives” and other such efforts to document Nazi atrocities.

This forms of documenting tragedy is especially notable, but there is also a dramatic transformation: Heye ‘im pefiot was specifically not an archive, but actually produced news articles that were modeled on liturgical poems; they followed an example of addresses to God, now directed at the Jewish philanthropist Edmund de Rothschild who they hoped would come to the aid of the Russian pogroms. Simon Dubnoqw’s 1903 Kishinev inquiry was conducted as a survey, similar to later ethnographic expeditions of S. An-sky. But Hayyim Nahman Bialik’s findings were not used to immortalize Kishinev in history, but rather in literature, composing the epic poem “Ba-‘ir he-haregah” (In the City of Slaughter).

It is thus remarkable that the Tcherikower and Ringelblum initiatives specifically framed their activities as archives. From 1892 to 1942, archives shifted from not being in the places where one might expect them (i.e. in historical societies) to being everywhere, with the term “archive” being applied in a much more universal and broad fashion.

The Emergence of Jewish Archives, As Archives

Against this broader backdrop we find that in the first decades of the twentieth century, Jews increasingly sought to gather together historical archives, as archives. That is to say, Jews in different communities did not just document their past but increasingly placed them under the rubric of an “archive.”

This manifested itself in the first major professionally-managed Jewish archive, the Gesamtarchiv der deutschen Juden, which was first envisioned in 1903 by Ezechiel Zivier and opened in 1905 under the leadership of Eugen Täubler in Berlin. As Zivier put it in his initial call: “Every great people aspires to have an archive of their antiquities.”

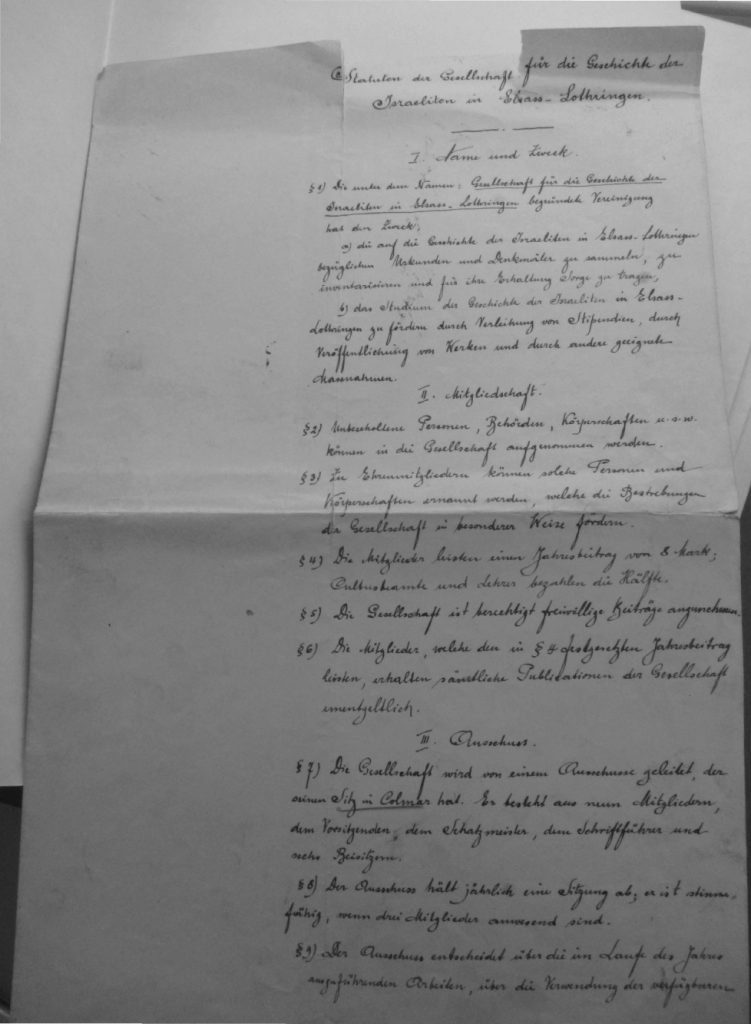

This turned out to be somewhat prophetic, because in the aftermath of the formation of the Gesamtarchiv, Jews around the world looked to this example and tried to create their own archives on its model—and in fact even when people opposed the Berlin archive, they did it by creating a competing archive of their own, as was the case of Moïse Ginsberger’s Société d’histoire des Israélites d’Alsace et ed Lorraine (Historical Society of the Jews of Alsace and Lorraine).

In the course of the twentieth century, we find that Jewish communities—on a local level, and also regionally and nationally—all turned towards archives as a critical form through which they would document and preserve their history. These records were brought together consciously, and called archives, which is important for us to understand the differences between longstanding Jewish recordkeeping—from which many of these documents derived—and their reframing as archives. In doing so, the process of gathering Jewish cultural and historical materials transformed them into history because they were marked and coded as part of the past as opposed to something which should be used day-to-day.

This process began prior to the Second World War, but it only increased and accelerated in the aftermath of the Holocaust. With the destruction of European Jewry, and the concomitant Nazi program of looting and plunder in which Jewish libraries and archives throughout Europe were decimated and their contents scattered or destroyed, what would happen to all of these priceless records and other historical treasures? The process of rebuilding Jewish archives in the aftermath of the Holocaust meant that these files were now up-for-grabs and could be transferred to new places: Creating Jewish archives thus was part of the reorientation of Jewish culture in the aftermath of the Holocaust as the files could be re-ordered to reflect a new order of Jewish life and its landscapes.

In the course of the twentieth century, one can thus identify the wide proliferation of archives in Jewish cultures, as Jews sought to gather together the files of their past, specifically calling them “archives.” This process reflected the rising value of these materials as Jews sought to preserve them for posterity and the materials thus accrued new value and meaning to the point where people were willing to fight over who would get them and where they should go.

This is the core of what we mean when we discuss the idea of a “time to gather” in modern Jewish cultures: the ways in which Jews sought to gather together the sources and resources of Jewish life in times of rapid change, and the proliferation of these activities as archives, when Jews specifically looked to archives as a framework that gave meaning and value to the materials they collected. The book A Time to Gather: Archives and the Control of Jewish Culture focuses on this phenomenon in three key countries—in Germany, the United States, and Israel/Palestine—where there was a distinctive archival network and struggle over what should happen to these archives. But we can see this phenomenon of the proliferation of Jewish archival activities as a global phenomenon in all places where Jews have lived, and one which is continuing as Jews the world over continue to create archives of their history.

Toward an Archival Perspective on Jewish History

This brief overview of the history of records and archives in Jewish cultures has indicated, first, that recordkeeping has been a constant factor in Jewish life throughout the ages. It is simply not true that Jews did not have archives prior to modernity; at the same time, there is something distinctive about the ways in which Jews have preserved their past, and thus encountered and engaged with it, in more recent times.

Altogether, we can begin to understand how we can have an archival perspective on Jewish history. Certainly, much of Jewish history is studied through archival sources. But more specifically, it is to see the ways in which archives have been active players in Jewish history and culture.

Traditionally, people understand records as a reflection of historical events. For instance, a group has a meeting, and someone takes down notes of what was discussed. However, we can also understand the ways in which the recordkeeping process, and the efforts to preserve them, influenced history itself:

The charters and privilegia were not just telling what happened, but were active forces in the ongoing situation of Jewish life in the different locales where Jews lived under their protection. When police surveilled Jewish political figures and organizational leaders in the nineteenth century, it was not just a way that we can learn about what happened at those meetings or in discussions in cafés. The fact that people were being monitored—of which they were aware—meant that the act of police reporting affected the ongoing development of modern Jewish politics. And the efforts to gather together archival materials, both in the course of the twentieth century and into our present moment, does not only reflect the changing factors of Jewish life around the world, but also contributes to the ways that Jewish communities and groups seek to display their dominance over Jewish culture and the possibility to direct the Jewish future.