Jump to:

- The Short Answer

- The Somewhat Longer Answer

- How Documents Become Archives

- How Archives Became Everything

- “What is an Archive” in the Context of this Research Guide

The Short Answer

“What is an archive?” It might seem fairly obvious: Archives are places that hold historical materials that we use to study the past.

But it doesn’t stop there. There’s a reason why so many books and articles have been written about archives, and it’s because “archives” have come to represent so many different things in our information-age society. It’s not just that archival theory can be complex and arcane (which it can be). Not only have archives themselves multiplied (both in Jewish cultures and beyond), but the term itself has proliferated and appropriated varied meanings. For instance, one can differentiate between archives as institutions, and archives as historical materials themselves. Entire industries are also built upon archives: The media empires of the twenty-first century, like Netflix and Spotify, essentially are media archives that one pays to access; and the contemporary capitalism thrives on gathering and storing information, essentially creating an archive on each of us. In a world where millions of people are categorized as “undocumented,” it becomes clear that archives and archival documentation has come to have a crucial role to play in all aspects of our lives. As such, archives are not just a place or a thing, or even about history. They can be a mode of thinking about the power of information in society—both in our own day, and how this has functioned throughout history.

In sum, “what is an archive” is a hard question to answer can identify a proliferation of archives, both as institutions and ideas, which reflects the attractiveness of archives in both Jewish culture and beyond.

One might think that parsing the diverse meanings of archives—and of “Jewish archives,” for that matter—is pedantic or pointless, a purely intellectual exercise. By contrast, it reflects the productivity of thinking about archives at large as powerful and important sources of history, and forces in society both past and present, too.

The following overview—a somewhat longer answer to a seemingly simple question—is intended to offer a basic explanation of what historical archives are, especially for those who aren’t familiar with them or who haven’t spent time doing research at archival institutions. It also seeks to illustrate some kinds of archives we might talk about, and identifies the specific sorts of archives that this guide is focused on in more specific terms. And finally, it seeks to overview briefly how scholars approach archives, both as historical sources and also as sites for critical inquiry—indeed, there are entire books on it (including A Time to Gather).

The Somewhat Longer Answer

Colloquially speaking, an archive is a collection of old things, but simultaneously it’s a ubiquitous term of our information age. This may seem paradoxical—archives representing ideas about both the old and the new. But it highlights what archives are, and what they have become: The terminology of archives has come to mean many different things. Here, we will articulate a few ways we can understand archives, and what they constitute in practical and intellectual terms.

To return to the central question: An “archive” can refer to (a) archival institutions, which are institutions or organizations specifically dedicated to holding historical materials; (b) archival collections, which can be both sets of historical materials related to a specific topic, person, or institution, and usually of common provenance—but which are sometimes held by an archival institution, and sometimes are not; and (c) archival materials, which make up archival collections but are not necessarily organized in any collection. In fact, any historical document can be called “archival materials” colloquially, but we should differentiate between those which are just materials relating to the past and those which have been termed an archive. This distinction between “historical materials” and “archival materials” might seem pedantic. But the distinction is tied to a definitional difference as people—whether scholars, archivists, or general members of the public—have deemed the materials to have a certain value and purpose, a transformation in how they are perceived and preserved.

All of us have archives of our own: We have a stack of old bills; a folder holding birth certificates, marriage licenses, and other vital records; or even just the emails accumulating on our laptop. All these things are archives—both in terms of the actual files, and the collection as a whole—even if they are not held in a historical archival institution. Moreover, all businesses or administrative operations will have a collection of their records which are consulted day-to-day; this is also an archive, what some archivists have termed a working archive. At some point, these materials, whether held by a person or by an administrative entity, might be transferred to a historical archive which has the aim of preserving these materials for posterity.

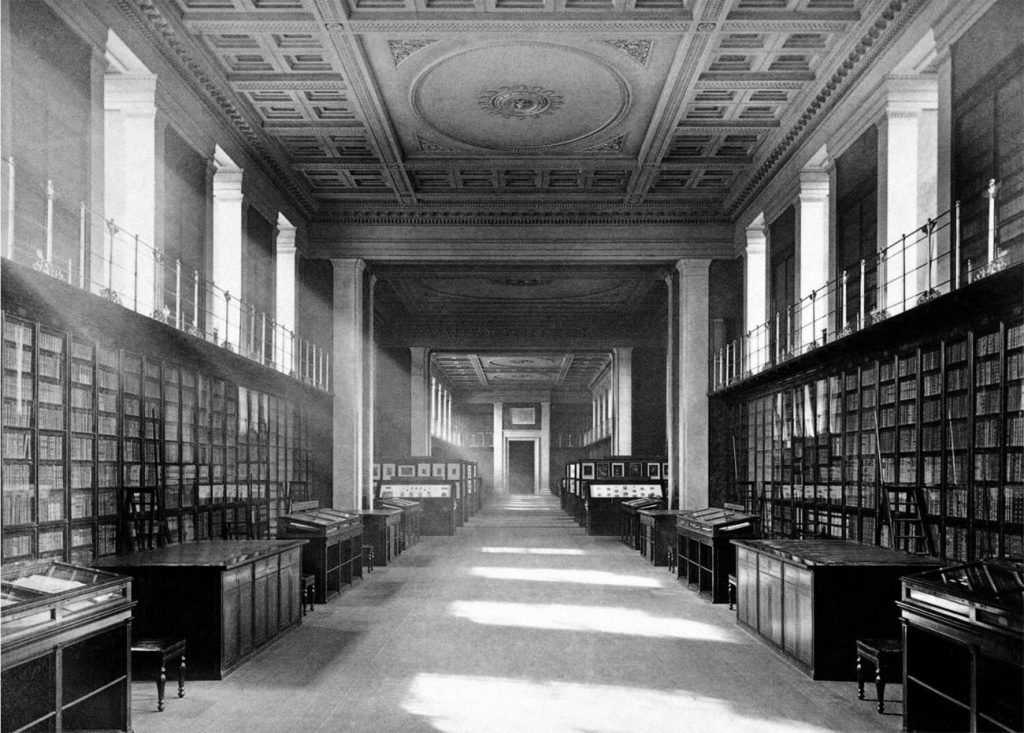

This is what, in practical terms, most people talk about when they think about archives: institutions or repositories that house the records and materials of the past. Without these archives, our knowledge of history would be greatly impoverished; as the one nineteenth century author put it, “no archives, no history.” Archivists gather historical records, process and catalogue them, and make them available to researchers, often in a reading room but also these days sometimes digitally. Files are organized into collections, ideally stored in climate-controlled stacks, and researchers can order specific boxes or files based on a finding aid, which describes the materials in the collection. These archives are in the business of collecting historical materials, but they don’t collect everything. In fact, they have very specific curation missions and have limited resources to process or appraise and describe the materials. As a result, many archives actively seek to de-accession historical materials, even though we tend to think about archives as being in the business of bringing together historical materials.

Sometimes, a great deal of the material in an archive is unprocessed, meaning that the archivists have not yet fully appraised the documents and collections to determine what is in it or create a guide to the materials. When scholars talk about the excitement of working in archives, oftentimes it is precisely this process of discovery: Traveling to an archive, working there long enough to gain an intimate familiarity with the materials, and finding something remarkable that no one knew was there in the first place.

Archives, as dedicated institutions, can be distinguished from libraries and museums. But they can also overlap, as libraries and museums often have archival departments too, sometimes referred to as special collections. Usually, archive repositories are dedicated to one-of-a-kind materials, rather than items like books which have had many copies printed and thus different libraries might each have a copy. Also, archival materials tend to be primary source historical materials which were created directly by an individual or group, which are kept together as a collection when they are transferred to an archive (though, especially as we see in the history of Jewish archives, often these collections are broken up). But when people had their own book collections, sometimes those books are purchased or received by an archive when they take that person’s archival materials, meaning that many archives have libraries, too.

Part of what makes the question “what is an archive” complicated is that the term can represent both an entire institution or repository, and it also can mean a collection of materials—which can be housed in an archival institution, held by an individual person, or even just sit in someone’s filing cabinet. Ultimately, anything can be an archive, as it can be a collection of any kind. But, crucially, one can talk about a moment of transformation when something becomes an archive: when files transition from active day-to-day use to serving as references for things past, or when those who gather a collection specifically decide to call it an “archive” as opposed to something else. When we talk about “what is an archive,” then, the challenge is to think simultaneously about how archives are an entire way of thinking about information, and also something which people can actively call an archive.

One way to illustrate the matter when and how to call something an archive might be to look at the example of the Cairo Genizah, the famous store-room from the Ben-Ezra synagogue in Cairo which made its way to Cambridge and other western universities around the turn of the twentieth century. Important twentieth-century Genizah scholars like S. D. Goitein famously declared that the Genizah was not an archive. Indeed, Goitein called it an “anti-archive,” because it was a store-room for unused and unorganized documents and manuscripts—while he thought that archives were meant to be studied, and were organized. These days, many people talk about the Genizah as an archive: Stefan Reif, the longtime leader of the Taylor-Schechter Genizah Unit at Cambridge University, wrote a book titled An Archive from Old Cairo, and Marina Rustow’s recent book about the Cairo Genizah was titled The Lost Archive. So which is it: Archive or not archive? One might say that the Genizah was not created as an archive by those Jews who stored files there, but it has been used as an archive by modern scholars. In this way, we can talk about how a collection (or documents as a whole) can become an archive over the course of time.

How Documents Become Archives

Jacques Derrida famously wrote about the “moment of archivization,” which can refer to when an idea is written down or recorded (i.e. when it is set down to an “archival form”)j; or to the broader transition from a “working archive” to a “historical archive.” This general transition, as something becomes an archive, is important because it is in this process that objects—written documents or otherwise—are given new meaning and are attributed greater value, now that people feel that they should be preserved rather than discarded.

Some archival science scholars have described this process as a documentary “life cycle,” as individual pieces of paper (or even digital documents) make their way from their birth (i.e. when they are originally produced) to being deposited in an archive. Recently, some scholars have argued that this “life cycle” model is overly simplistic and implies that archivists passively take documents into their custody, when this is not the case: Archivists can (and many argue, should) take an active role in collecting materials of historical interest, for instance helping to photograph protest signs as the protest is happening, not after it is already over, what has been termed a “records continuum.”

This “post-custodial” model has come into vogue in the past 50 years or so. It all represents the continuing development of archival science, the professionalization of archival practices that began to emerge at the turn of the twentieth century, around the time of the first professional archivist societies in Belgium, the Netherlands, and elsewhere as archivists sought to standardize their practices around principles like “respect des fonds” (literally, respect for the files) or the “provenance principle,” both of which essentially argued that archivists have a duty to keep files in their original order, in order to preserve their historical integrity.

All of this represents the idea that there is a different “archival mode” of operation for how we treat things which have become archives. It all stands at the center of the way in which historical materials accrue value and thus become things which people are willing to fight over: who should have them, where they should be, and what it means to “own” history and culture.

How Archives Became Everything

What is particularly exciting about archives is that we can speak about archives not only in the context of historical research, but also in many other spheres of life. In fact one might argue that in our own information age, archives have become a dominant force shaping politics, business, and society at large: In 2016, the U.S. presidential election hinged on the illicit leaking of an email archive. Social media empires are built upon the process of tracking individuals across the internet, and big data drives business decisions in retail and other diverse sectors of twenty-first-century capitalism. And as the phrase goes, “pictures or it didn’t happen”—we live in a world where everyday people are documenting their lives in order to create their own archives, whether we talk about taking photos of their food or anything else; alternately, most everyone understands that anything you post on the internet will be there in perpetuity.

Altogether, we find that archives and data are critical components of our contemporary society. In this respect, the terminology of archives has expanded far beyond the dusty reading room; and alongside this, we can use archives as a way of thinking about all sorts of social phenomena far beyond historical study. It might be productive to begin calling everything an archive, and to use archives as lens through which to understand all aspects of a society driven by data and those who control it. In this context, scholars speak not just about “an archives,” but also often fixate on “the archive” as an idea and as a social force.

That is to say, alongside the practical meaning of archives, there is also the way that the terminology and the idea of archives have become a malleable and flexible term for entire ways of talking about evidence, history, and society. First of all, scholars often talk of going to “the archives” as a generalized way of saying they have been doing archival field research. But many writers have also explicated the idea of “the Archive” as a theoretical framework, expanding the idea of archives beyond institutions to reflect entire social processes. Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida, pioneering figures of poststructuralism and postmodernism in the 1960s, ‘70s, and beyond, spearheaded this idea. Foucault, who was interested in the notion of discourse—the way that the structure of language set the terms of social debate—wrote about “the archive” as the limit of what can be said. Derrida was also interested in archives and their relationship with memory, most famously in his meditative essay “Archive Fever” (Mal d’archive), which he presented at a 1994 conference at London’s Freud Museum.

Many scholars, building upon these and other works, have taken “the archive” not just as an institution but as a tool of analysis for how society operates and the power of information writ large. The “imperial archive,” for instance, can been identified as a specific type of archival institution—i.e. the archives that stored administrative materials on colonial territories, and brought them to imperial capitals leading to the situation that the history of the colonized are in the hands of their colonizers. At the same time, such an “imperial archive” is also be a process whereby European empires collected information about their colonies and conquests. In this view, institutions like the British Museum, the Encyclopedia Britannica, and even the very effort at global exploration are clearly not “historical archives” in an institutional sense, but they are part of this “imperial archive,” an ongoing process of information-gathering in the service of the governance and expansion of empire. Especially in the context of the nineteenth century, for instance, when information did not move as quickly as it does today, the very possibility of imperial control depended on the ability to learn about and keep tabs on what was happening an ocean away.

In the past twenty-five years, some scholars have continued to expand the way we can talk about “the Archive” as a tool of theory—sometimes to analyze actually-existing archives, and also as a technique to consider all aspects of society. In this sense, anything can be seen as an archive: The trash is an archive of our daily discards; the earth beneath us and the fossils it contains is an archive of aeons past; ice cores present us with an archive of a changing climate; the night sky is an archive of the cosmos. When we start to identify everything as an archive, we can see both the varied sources of knowledge about the past that surround us, and also the ways in which these sources are always shaped by human experience. That is to say, as Foucault famously argued, our view of information does not exist on its own but is shaped by ourselves—we create our own ordering of the world. As archivists have increasingly understood the active role they play in the shaping of the historical materials they hold, we should understand that all of the knowledge which we have is mediated.

“What is an Archive” in the Context of this Research Guide

Given the many meanings of “archives,” it is useful to clarify what kinds of archives we focus on here, in the context of this research guide and the book A Time to Gather: Archives and the Control of Culture.

When we speak of the history of “Jewish archives,” broadly, we might trace the development of a number of diverse traditions of collecting and preserving historical materials in Jewish culture, like communal record keeping methods (pinkasim), religious traditions like the Genizah, or the ghetto archives of the Holocaust years. Alongside this, we can also look at the emergence of collecting practices and institutions that specifically called themselves archives—that is, they have become archives.

When we are concerned with the development of Jewish archives, it is interested in both of these matters: to understand the ways that historical materials have made their way toward the present, and also to comprehend the specific efforts Jews have made to preserve the past in archival institutions, i.e. efforts and initiatives that specifically called themselves archives. In doing so, Jews made a value judgment by considering this past to be history, and took on a series of assumptions about the best way to preserve this material, as archives.

Given this context, on a basic level, the research guide seeks to highlight the history of Jewish archives, broadly speaking, in order to contextualize the hundreds of archival institutions and collections that researchers have at their disposal today. It cannot be a comprehensive, encyclopedic guide that lists every archive—that is plainly impossible as there will always be something left out. So it focuses primarily on institutions dedicated to an archival mission, as opposed to listing all institutions or groups that hold some kind of archival collections.

A Final Note

Taken altogether, one might think about Jewish archives in a very expansive way. Certainly—as A Time to Gather argues forcefully—there is a distinctive attractiveness to try to create a totalizing overview of all Jewish archives, but it is plainly impossible to offer an exhaustive and encyclopedic resource. With that in mind, this research guide aims to focus on archival repositories and institutions as a whole, especially those that call themselves archives, and which are dedicated specifically to Jewish history.

This approach stems from the realization that, just as we might mark historical materials of all kinds as “archives,” but especially those which adopt the term itself to describe themselves, we should also consider the ways in which archival institutions might take upon themselves the framework of Jewish history. Archival institutions, collections, and materials might all relate to Jewish history even if they do not call themselves “Jewish,” but we are especially interested in this guide with archival repositories and collections that (a) call themselves archives, and (b) think of themselves within the framework of Jewish history.