The Central Zionist Archives (CZA; הארכיון הציוני המרכזי) is the main archive dedicated to the history of the Zionist movement, its constituent organizations and institutions. It was founded in Berlin in 1919 by Georg Herlitz and is today based in Jerusalem, where it is located conveniently next to the central bus station. The CZA holds some of the most significant collections on the institutionalized Zionist movement, including the central offices of the Zionist Organization in Vienna, Cologne, and Berlin, as well as numerous Zionist federations and organizations like Hadassah, the Zionist Organization of America, and the Jewish Agency (which is the parent organization of the CZA today). They also hold personal files of Theodor Herzl, David Wolffsohn, and other leading figures.

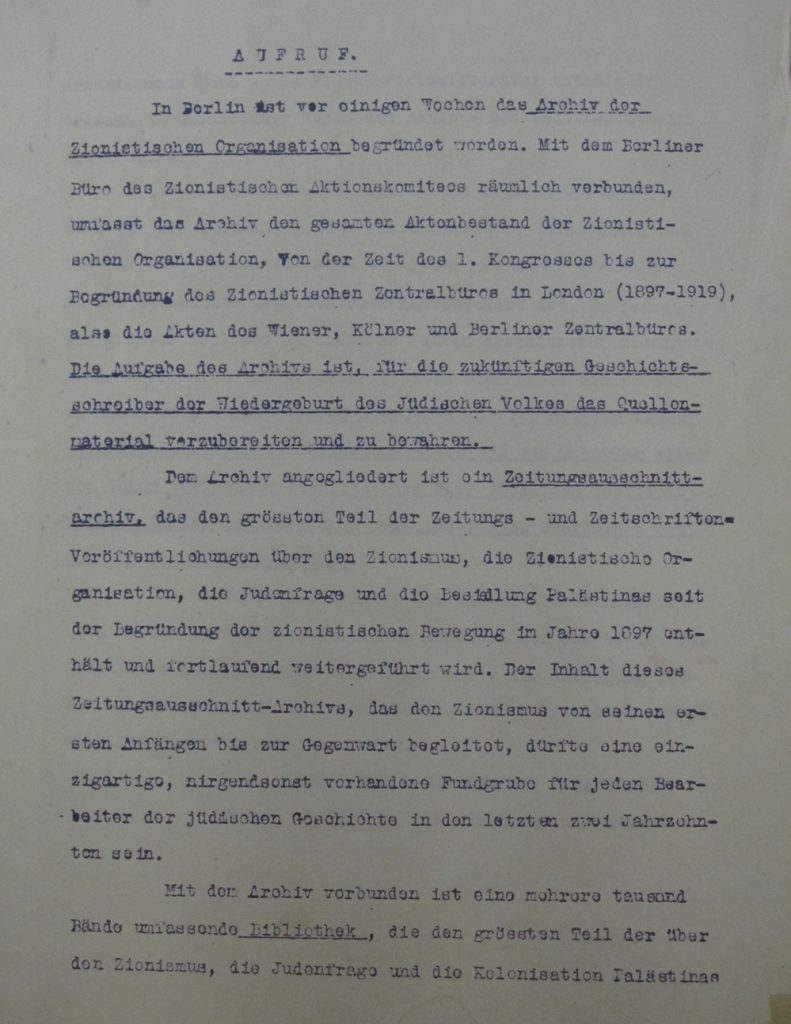

As early as 1899, the Zionist Organization considered forming an archive to document the nascent Jewish nationalist movement. It would only be 20 years later, in 1919, that the Zionist Organization’s Berlin offices established the Zionistisches Zentralarchiv (Zionist Central Archive) under Georg Herlitz.

Herlitz, who had been an assistant to Eugen Täubler at the Gesamtarchiv, joined the Zionist Organization that year and took on the archive at the urging of Arthur Hankte. Berlin was at the time no longer the central office of the Zionist Organization, which during World War I had relocated to Copenhagen; consequently, creating an archive and trying to centralize files there was part of the group trying to reassert itself at a time of struggle between Zionist leaders in different countries for the direction of the Zionist movement, most famously between Louis Brandeis and Chaim Weitzman in the United States and Great Britain respectively. There was also an effort to create a Zionist archive in New York City, under

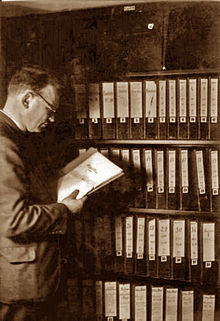

Herlitz’s archive initially held the files of the Berlin office, but over the years it came to include the records of other Zionist federations as well, truly becoming the central archive of the worldwide Zionist movement.

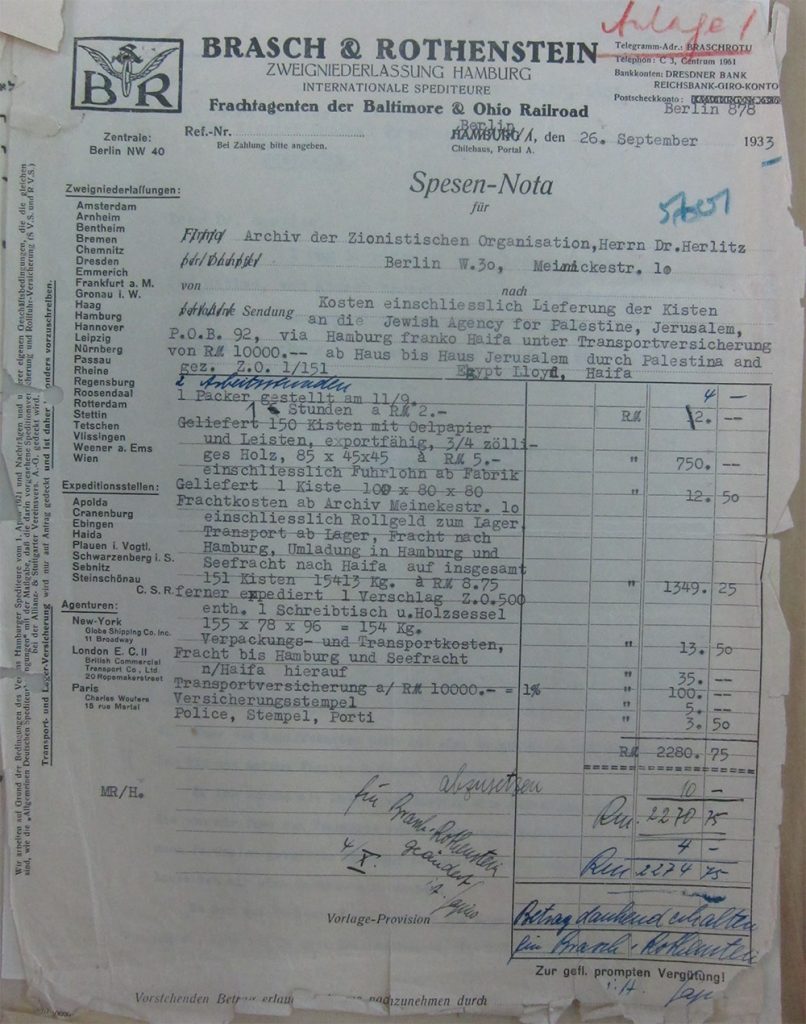

In the 1920s, Jewish leaders in Palestine tried on a number of occasions to transfer the Zionist Archives to the National Library in Jerusalem. However, it was only in the Fall of 1933, after the S.S. set up a barracks across the street from the Zionist Organization’s Berlin offices, that Herlitz and the files made their way to Jerusalem. There, however, Herlitz found that there was little space or funding to re-establish the Zionist Archives, leading the files to languish in cold storage in the basement of the King George Street offices of the Zionist Organization until 1935, when Herlitz together with Alex Bein re-opened the Central Zionist Archives.

Together with Bein, who was himself a German Jew and a former archivist at the German Reichsarchiv in Potsdam, they expanded the Zionist Archives with the aim of documenting not just the Zionist Organization but also Jewish settlement in Palestine and acquiring the files of leading Zionist figures including Theodor Herzl, whose papers Bein acquired in 1937. Following the Second World War, Bein traveled to Europe to search for relevant files, which he acquired alongside materials for the Jewish Historical General Archives (today the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People).

In 1955, Alex Bein became both Israel’s first State Archivist and the director of the Central Zionist Archives, positions which he held jointly until 1970. In this capacity, Bein asserted the position of the CZA as the leading archival institution in the country and the most prominent of a series of “public archives.”

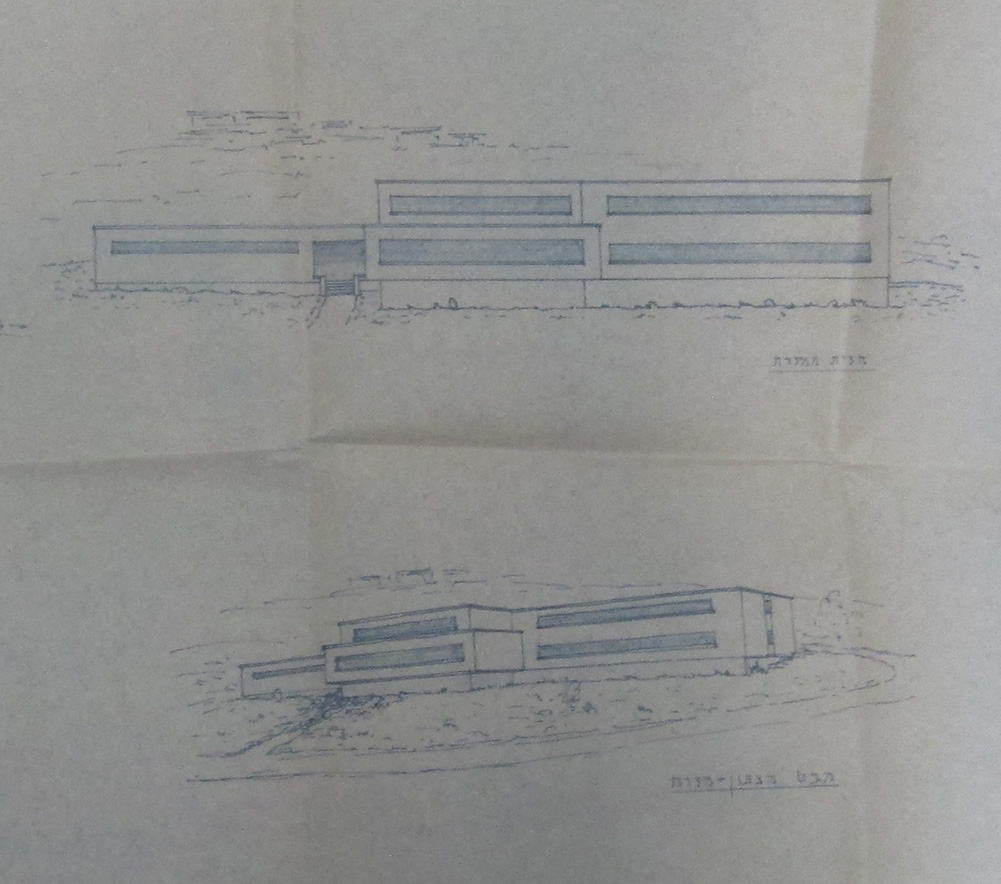

In the 1960s, Bein tried to establish a new building for the CZA to accommodate its growing collections, and secured a location adjacent to the Knesset. (In fact, this plot of land is the exact same location where the new National Library will be once its construction has completed.) Under various plans for a “national archives building,” it would have been joined by the Jewish Historical General Archives and Israel’s State Archives. However, following the 1967 Six-Day War, this plan was shelved. It was only in 1987 that the CZA’s current building was opened to the public, adjacent to Jerusalem’s Central Bus Station and the Binyanei Ha-uma convention center.

Research Notes

The CZA is centrally located in Jerusalem, accessible from the bus station and thereby from throughout Jerusalem by various bus lines, as well as from other locations throughout the country. Researchers can walk to the CZA from the bus station via an underground tunnel that allows one to bypass major highways.

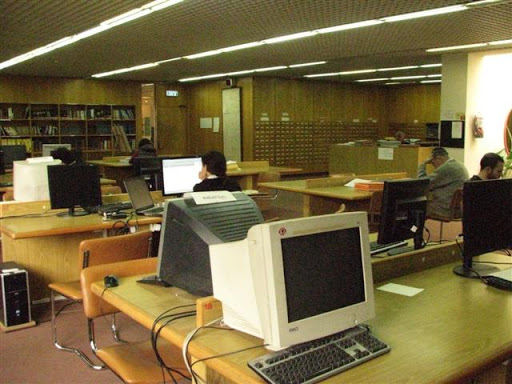

The CZA has a set of lockers in the main foyer outside the reading room, where researchers can deposit their bags. Scholars can bring their computers and cameras into the reading room, and there are numerous plug locations where one can charge their computer and camera batteries.

There is a main reference desk in the entrance to the reading room which is continually staffed. There are also card catalogues and printed finding aids for the collections.

The Central Zionist Archives have digitized a large portion of their collections. Digitized records can only be accessed via the computer system, unless the scholar has a very specific reason to consult the originals. This includes the records of Theodor Herzl, which were digitized at the highest resolution of all the collections. The best way to digitally capture these materials, unfortunately, is to photograph the computer screen.

Researchers also use the on-site computers to order files, which are brought from the stacks at set times during the day. Scholars can leave materials with the reference desk for coming days, which are stored in a back room adjacent to the reading room; one can thus order files at the end of the day to ensure that there will be research materials when they arrive the next morning.

There are a number of semi-private research cubicles at the back of the reading room, where there are computers and microfilm machines.

The CZA does charge for photography, on a per-photograph basis. Scholars are asked to fill out a form and pay for photos after each day of research.

Researchers can consult a list of finding aids online, and also there is an online search engine on the CZA’s website.

Further Reading

- Jason Lustig, A Time to Gather: Archives and the Control of Jewish Culture, ch. 2

- Michael Heymann. “’Arkhiyon Herzl.” Arkhiyon: Miḳra’ot le-’arkhiyona’ut u-le-te’ud 11–12 (1999): 17–41.

- Robert Jütte. Die Emigration der deutschsprachigen “Wissenschaft des Judentums.” Die Auswanderung Jüdischer Historiker nach Palästina, 1933–1945. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1991.

- Georg Herlitz. Mein Weg nach Jerusalem: Erinnerungen eines zionistischen Beamten. Jerusalem: Verlag Rubin Mass, 1964.