The archives of the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU) contain records on the history of the AIU and its activities. They document its school system and other philanthropic and cultural activities, and thereby the history of Jewish communities across the Middle East and North Africa.

The Alliance Israélite Universelle, established in Paris in 1860, emerged at the intersection of Jewish solidarity with the “eastern” Jews of the Middle East and North Africa (especially following the Damascus affair of 1840) with French imperialism and its “civilizing mission” (mission civilatrice). At the same time, the AIU inserted itself into the politics of modernization and colonization taking place across the region, particularly given the Ottoman Empire’s interest in westernization under the Tanzimat reforms of 1839 and 1856, which specifically called for educational reform, and also France’s growing colonial involvement in North Africa.

The group’s influence derived primarily through the school system they created. By World War I, close to 14,000 Jewish children were enrolled in 183 AIU schools, which were mostly elementary schools. The AIU also formed a teacher’s college in Paris, the École Normale Israélite Orientale.

The AIU sought to “improve” the status of Jews in the Ottoman Empire and other Middle Eastern and North African territories by modernizing and Europeanizing them. The teachers and school officials sought to inculcate a Francophone cultural orientation French republican ideology in the interst of “regenerating” these “eastern Jews,” borrowing the terminology of debates surrounding the transaction of emancipation of the Jews in France from the turn of the nineteenth century. This was especially potent in places like Algeria, where Jews became French citizens following the 1873 Cremieux decree, but French Jews did not believe that Algerian Jews were “French” enough.

Consequently, the AIU and its schools and other cultural/political programs situated itself as a key player in the changing status of Jews in various countries across the Middle East and North Africa; and the AIU and its ideology came to represent one component of a three-way tension over the cultural and political orientation of Jews in many of the countries and territories of the region: To what extent would Jews feel themselves to be part of the emerging local nationalistic sentiment, to be part of Jewish nationalism, or to commit themselves to what some scholars have termed an “Allianceiste” approach to Jewish culture with a Francocentric perspective.

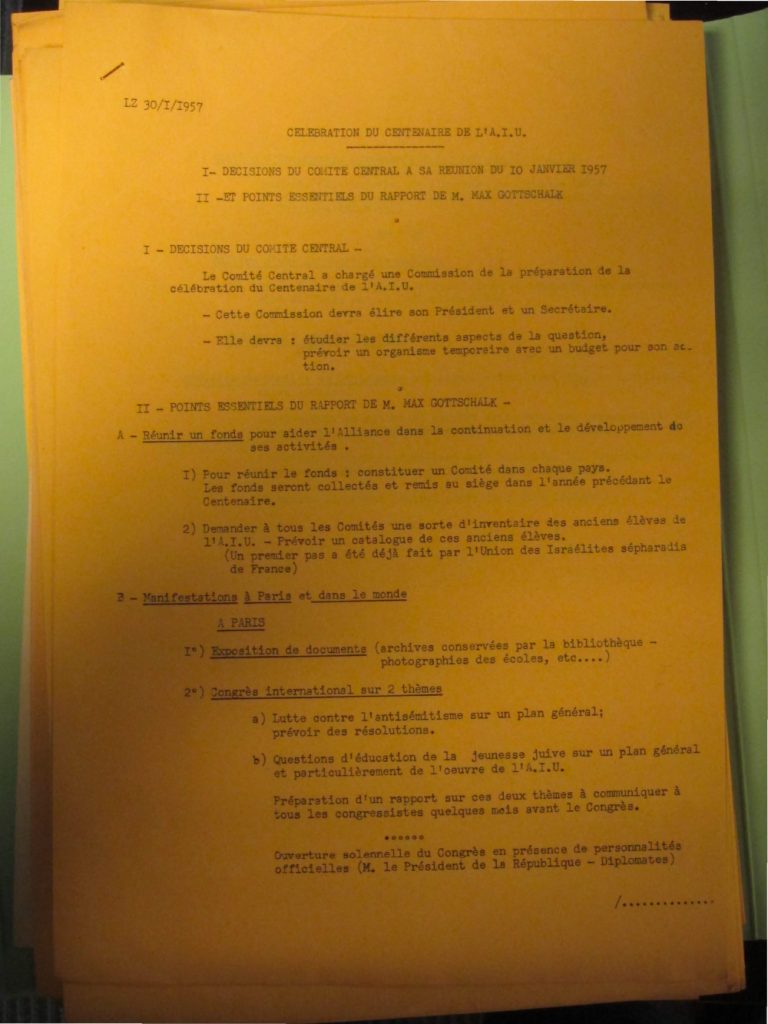

The activities of the AIU and its interest in reporting and documenting the status of Jews in different locales makes the records of the AIU an important resource both for the study of French Jewish history as well as Jewish history across the MENA region. The AIU understood the value of its records and in the 1950s, and with the upcoming centennial of the organization in mind they commissioned Georges Weill, a French-Jewish archivist based in Strasbourg, to organize the materials so they could be used for research. Consequently, we can speak of the formation of the AIU archives at this time.

Notably, the AIU faced a major challenge in cataloguing its files because their library had been looted by the Nazis, who took many records to Berlin. At the conclusion of the Second World War, these historical materials were seized by the Soviets, part of a wider phenomenon known as “twice-looted archives”—the way in which the Nazis stole records and archives, but instead of being restituted or returned, the Soviets stole them a second time and brought them to Moscow. According to a 1992 agreement, these files were returned to France; they arrived in 2001, with microfilm copies remaining in Moscow.

Research Notes

The AIU archives are located in the main library of the Alliance Israélite Universelle in Paris, on the basement level of the AIU’s headquarters on rue Saint Georges.

Researchers can make requests for archival materials at the main reference desk, and are permitted to take photographs of archival materials.

Finding aids can be consulted in print in the library; scans of many of the finding aids are also available online, and also can be searched in the archives’ online database.

Further Reading

- Jean-Claude Kuperminc. “La Reconstruction de La Bibliothèque de l’Alliance Israélite Universelle, 1945–1955.” Archives Juives 34, no. 1 (2001): 98–113.

- Georges Weill. “Les archives de l’Alliance israélite universelle et les sources de son œuvre scolaire.” In L’Enseignement français en Méditerranée: Les missionnaires et l’Alliance israélite universelle, edited by Jérôme Bocquet, 51–56. Rennes: Presses Univ. de, 2010.

- Lee Shai Weissbach. “The Library of the Alliance Israélite Universelle.” French Historical Studies 14, no. 2 (Fall 1985): 274–75.

Further Reading on the Alliance Israélite Universelle

- Aron Rodrigue. French Jews, Turkish Jews: The Alliance Israélite Universelle and the Politics of Jewish Schooling in Turkey, 1860-1925. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990.

- Lisa Moses Leff, Sacred Bonds of Solidarity: The Rise of Jewish Internationalism in Nineteenth-century France. Stanford University Press, 2006.